In this post, Allan Hazlett discusses the article he recently published in Ergo. The full-length version of Allan’s article can be found here.

Shame is a familiar human emotion. Most people have been ashamed of something they have done or of some fact about themselves. Of course, sometimes people feel shame when they should not. Social norms cause people to be ashamed of their bodies, for example, or about being gay. In these cases, although our shame is real, the thing we are ashamed of isn’t really shameful. Our shame, then, is not “fitting,” as contemporary philosophers would put it. Just like it is fitting to be afraid only of what is dangerous or threatening, so it is fitting to be ashamed only of what is shameful.

But is shame ever fitting? Is anything really shameful? I think so. I once drank too much wine and ate a bunch of my kids’ Halloween candy. Of course, because they had been keeping careful inventory of it, they found out. That was shameful, to eat their Halloween candy, and I was ashamed of having done it. My shame, in that case, was fitting and appropriate.

In my paper, “From Doxastic Blame to Doxastic Shame”, I argue that it is sometimes fitting to feel shame for having believed something. Actions like eating your kids’ Halloween candy can be shameful, but so can beliefs. I think this is an interesting conclusion, in part, because it sheds light on a long-standing debate in philosophy about whether it is ever fitting to blame someone for their beliefs. This debate, in turn, is connected to how, in general, we can evaluate or criticize people for their beliefs.

A central worry about blaming someone for their beliefs is that we don’t seem to be responsible for our beliefs in the way that we are responsible for our actions. The wine notwithstanding, I chose to eat that Halloween candy. But we do not and cannot choose to believe something. I don’t know where Tom Cruise is right now, but he might well be in Paris. Even so, I cannot choose to believe that he is in Paris – not, at least, in anything like the way I chose to eat the Halloween candy.

However – and this a key idea in the paper – it is sometimes fitting to feel shame for things that you are not responsible for. To see this, we need a different example (since I was responsible for eating my kids’ Halloween candy). Here’s an example I use in the paper: you might be ashamed of the fact that you are selfish, even though you are not responsible for being as selfish as you are. In other words, we can appropriately feel shame about our personality traits even though we don’t choose our personality traits. While I believe that nothing can be blameworthy unless you are responsible for it, things can be shameful even though you’re not responsible for them.

Still, you might wonder, can beliefs be shameful?

The example I use in the paper to support the conclusion that beliefs can be shameful is a case of racial resentment: for example, believing that White people are discriminated against more than non-White people. But I think it is also useful to approach this by thinking about embarrassing beliefs. (Embarrassment and shame are different, but related.)

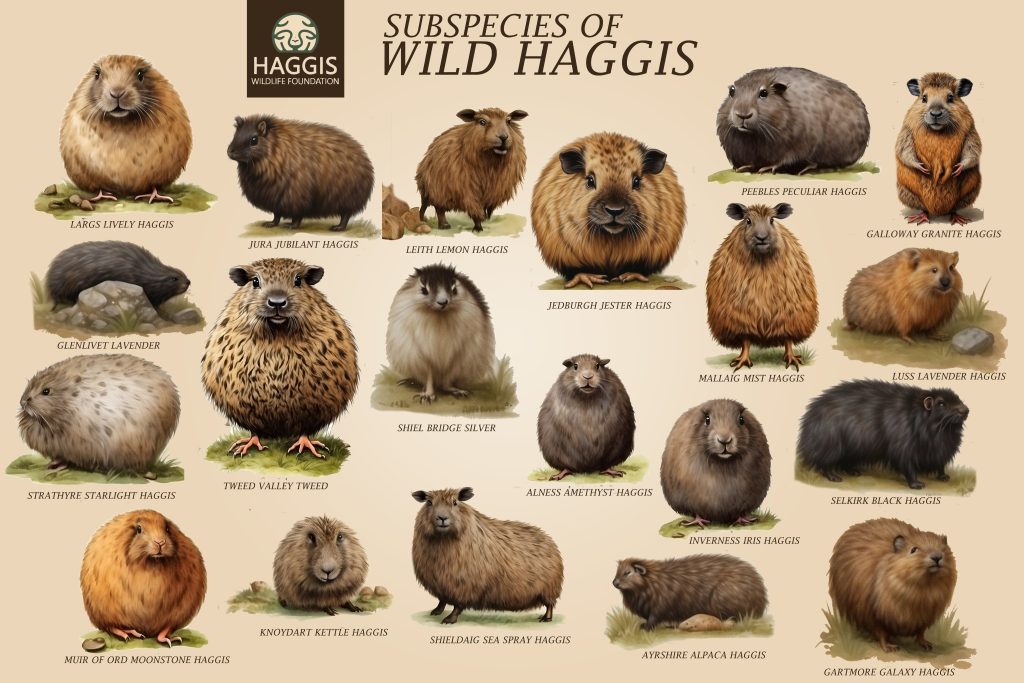

Have you ever been taken in by an April Fool’s joke or a fake news post? That can be embarrassing. In general, gullibility is embarrassing. When I lived in Scotland, my friends would tell American tourists that haggis was made from a little furry animal, called a haggis, that lived in the highlands. Some of them believed it. That was embarrassing for them.

Was it shameful? Not quite. But I argue that when the moral stakes are higher – as in the case of racial resentment – what would otherwise be an embarrassing belief turns into a shameful one.

Want more?

Read the full article at https://journals.publishing.umich.edu/ergo/article/id/6915/.

About the author

Allan Hazlett is Professor of Philosophy at Washington University in St. Louis. He works on several topics in epistemology, metaethics, and moral psychology. He is the author of many articles and three books, the most recent of which is The Epistemology of Desire and the Problem of Nihilism (Oxford University Press, 2024).