In this post, Paul L. Franco discusses his article recently published in Ergo. The full-length version of Paul’s article can be found here.

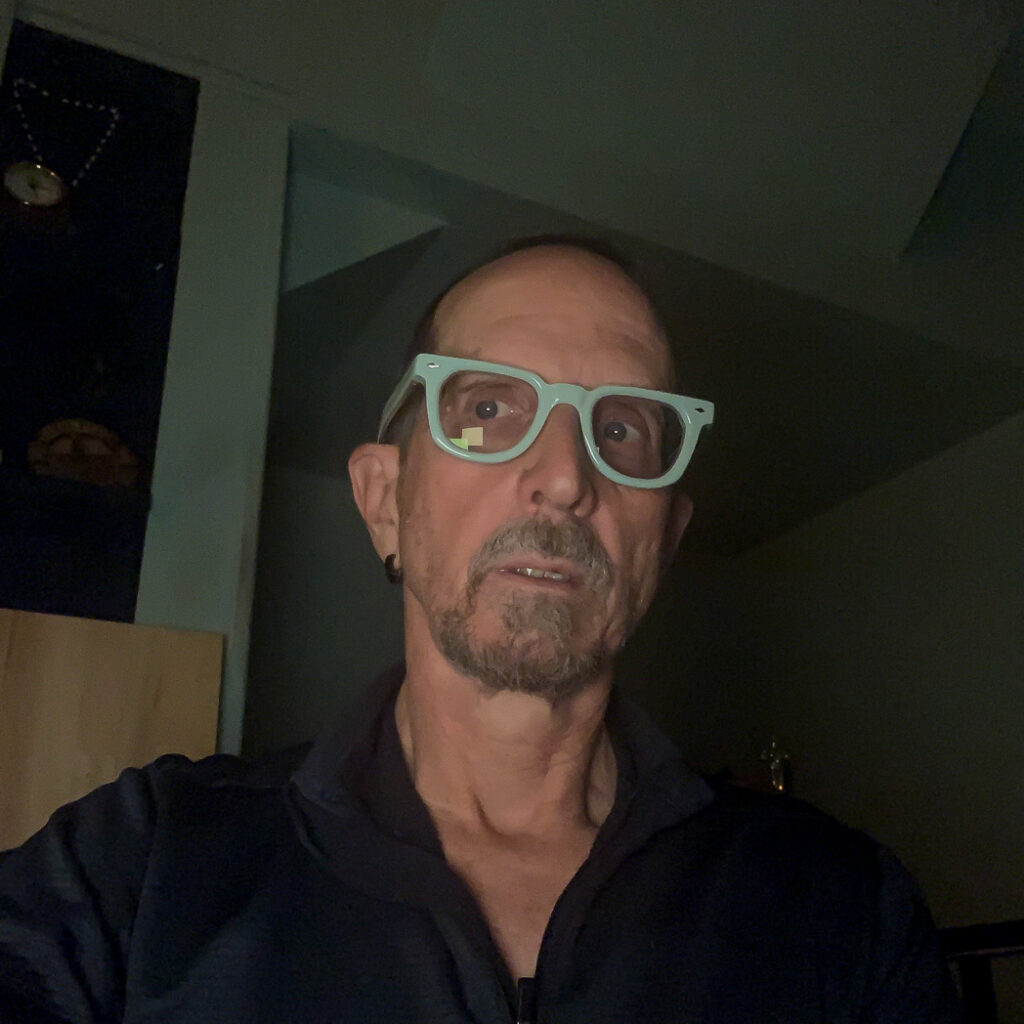

photographed by Howard Coster (1939) © National Portrait Gallery, London

In anthologies aimed at giving readers an overview of analytic philosophy in the early twentieth century, we are used to seeing listed works by G.E. Moore, Bertrand Russell, Rudolf Carnap, and Ludwig Wittgenstein. But upon reading these anthologies it is not immediately obvious what, say, Moore’s common-sense philosophy shares with Carnap’s scientific philosophy. Moore waves his hands to prove an external world; Carnap uses formal languages to logically construct it. Yet, both belong to a tradition now-called analytic philosophy. Following Alan Richardson, I think an interesting question in history of analytic philosophy concerns how this happened.

One common story centers A.J. Ayer’s visit around 1933 to the Vienna Circle to study with Moritz Schlick, Carnap’s colleague and leading representative of the logical positivist movement. Ayer distilled the lessons from his visit in his book Language, Truth and Logic (1936). In a readable style – more accessible than the technical work of some Vienna Circle members – Ayer brought the good word of verificationism to an Anglophone audience, resulting in vigorous debate.

Like Siobhan Chapman, Michael Beaney, and others, I think that this story – although not entirely wrong – neglects Susan Stebbing’s role in shaping early analytic philosophy. She contributed through her involvement with the journal Analysis, which published papers on logical positivism before 1936. She was also a central institutional figure in other ways, inviting Schlick and Carnap to lecture in London. In contrast with Ayer, who admitted that the extent of his scientific background was listening to a Geiger counter once in a lab, Stebbing, like the logical positivists, paid close attention to science.

Stebbing’s sustained engagement with logical positivists in articles and reviews in the thirties is central to their reception in the British context. This work is also a core part of Stebbing’s rich output on philosophical analysis. For these reasons, her work illuminates early analytic philosophy’s development.

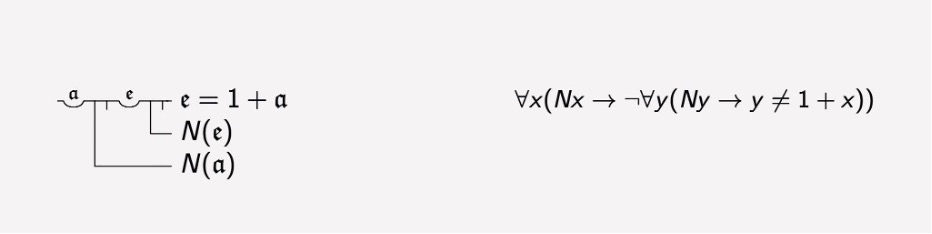

My paper reconstructs and interprets Stebbing’s criticisms of the logical positivist conception of analysis. The centerpiece is “Logical Positivism and Analysis” in which she contrasts her understanding of the logical positivist approach with the sort of analysis Moore practices. Stebbing argues that Moore insists on a threefold distinction between:

- knowing that a proposition is true;

- understanding its meaning;

- giving an analysis of it.

Accordingly, philosophical analysis doesn’t give the meaning of statements or justify them. Instead, it clarifies relationships between statements which are already known and understood.

Although she is not an acolyte of Moore, Stebbing agrees with the fundamentals of his account and contrasts it with the picture offered by logical positivism. On her view, the logical positivist conception of analysis – represented by Wittgenstein, Schlick, and Carnap – begins with the principle of verification. This principle says the meaning of a statement is its method of verification. To know a statement’s meaning is to know what verifies it, and philosophical analysis clarifies a statement’s meaning by revealing its verification conditions. Carnap was also committed to what he called methodological solipsism. This is the view that the verification of statements about physical objects and other minds is provided by that which is immediately given in phenomenal experience. Adopting this methodological commitment means that verification conditions reduce to first-personal statements about experience.

Stebbing asks how the principle of verification can ground communication in light of methodological solipsism. For her, the logical positivists should be able to answer. This is because they are interested in meaning and knowledge, and communication is necessary for intersubjective knowledge. Here, we come to the crux of her criticisms. She says that the identification of meaning with verification conditions collapses Moore’s threefold distinction. Then, she argues that in collapsing the distinction, and given Carnap’s methodological solipsism, the principle of verification gives counterintuitive conclusions about the meaning of statements about other minds and the past.

For example, on Stebbing’s account of logical positivism, the meaning of your statement “I have a toothache” is, for me, given in first-personal statements about my experience of your bodily behavior, your utterances, and so on. Similarly, the meaning of historical statements like “Queen Anne died in 1714” is given by first-personal statements about my experience when consulting the relevant records. After all, the verification theory of meaning identifies the meaning of statements with their verification conditions and methodological solipsism says those are found in statements about what is given in phenomenal experience. But Stebbing thinks this misidentifies knowing that a statement is true with understanding its meaning. For her, it is clear that you don’t intend to communicate about my experience in talking about your toothache. It is also clear that when you speak about Queen Anne’s death, you do not intend to communicate about the way I would verify it. Instead, in talking about your toothache, you intend to communicate about your experience; in talking about Queen Anne’s death, you intend to communicate about the world. Stebbing thinks that I understand the meaning of both statements because they are about the “same sort” (Stebbing 1934, 170) of things I could experience, even though I’m not currently experiencing them. For Stebbing, it is this “same-sortness” of experience which grounds our understanding of the meaning of statements about other minds and history, not our knowledge of their verification conditions.

These are just the basics; my paper has other details of Stebbing’s criticisms – and related ones by Margaret MacDonald –that I’m tempted to mention but won’t. Instead, I’ll close by explaining how paying close attention to Stebbing’s engagement with logical positivism can be helpful. As I see it, there are three main upshots.

First, we can better understand Stebbing’s novel contributions to the analytic turn in philosophy, especially her attention to the nuances of different types of philosophical analysis.

Second, we realize that the well-worn, presumed-to-be-devastating objection that the principle of verification fails to meet its own criteria for meaningfulness doesn’t appear in Stebbing’s work. Rather, she is concerned about whether logical positivism provides an account of meaning that explains successful communication. Whatever problems verificationism was thought to have, they were more interesting than whether the principle of verification is verifiable.

Third, by paying close attention to Stebbing’s focus on communication, we can better understand how her appeal to the common-sense conviction that we understand what we are talking about when we talk in clear and unambiguous ways is echoed in criticisms of logical positivism in ensuing decades – in particular, in the criticisms developed by ordinary language philosophers like J.L. Austin and P.F. Strawson.

Stebbing shaped the understanding of logical positivism in a way that made their brand of philosophical analysis recognizably similar to that of philosophers who didn’t share their scientific concerns. In doing so, she helped create the big tent that is early analytic philosophy.

Want more?

Read the full article at https://journals.publishing.umich.edu/ergo/article/id/5185/.

About the author

Paul L. Franco is Associate Teaching Professor in Philosophy at the University of Washington-Seattle. His research is in the history of analytic philosophy, the history of philosophy of science, values in science, and intersections between the three areas. He currently serves as the treasurer for HOPOS.