In this post, Cameron Buckner discusses the article he recently published in Ergo. The full-length version of Cameron’s article can be found here.

As far as kinds of thing go, representations are awfully weird. They are things that by nature are about other things. Van Gogh’s self-portrait is about Van Gogh; and my memory of breakfast this morning is about some recently-consumed steel-cut oats.

The relationship between a representation and its target implicates history; part of what it is to be a portrait of Van Gogh is to have been crafted by Van Gogh to resemble his reflection in a mirror, and part of what it is to be the memory of my breakfast this morning is to be formed through perceptual interaction with my steel-cut oats.

Mere historical causation isn’t enough for aboutness, though; a broken window isn’t about the rock thrown through it. Aboutness thus also seems to implicate accuracy or truth evaluations. The painting can portray Van Gogh accurately or inaccurately; and if I misremember having muesli for breakfast this morning, then my memory is false. Representation thus also introduces the possibility of misrepresentation.

As if things weren’t already bad enough, we often worry about indeterminacy regarding a representation’s target. Suppose, for example, that Van Gogh’s portrait resembles both himself and his brother Theo, and we can’t decide who it portrays. Sometimes this can be settled by asking about explicit intentions; we can simply ask Van Gogh who he intended to paint. Unfortunately, explicit intentions fail to resolve the content of basic mental states like concepts, which are rarely formed through acts of explicit intent.

To paraphrase Douglas Adams, allowing the universe to contain a kind of thing whose very nature muddles together causal origins, accuracy, and indeterminacy in this way made a lot of people very angry and has widely been regarded as a bad move.

There was a period from 1980-1995, which I call the “heyday of work on mental content”, where it seemed like the best philosophical minds were working on these issues and would soon sort them out. Fodor, Millikan, Dretske, and Papineau served as a generation of “philosophical naturalists” who hoped that respectable scientific concepts like information and biological function would definitively address these tensions.

Information theory promised to ground causal origins and aboutness in the mathematical firmament of probability theory, and biological functions promised to harmonize historical origins, correctness, and the possibility of error using the respectable melodies of natural selection or associative learning.

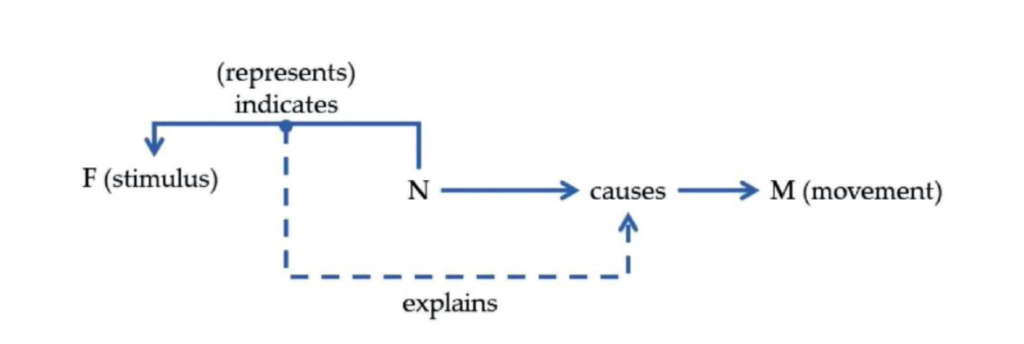

Dretske, for example, held that associative learning bestowed neural states with representational functions; by detecting correlations between bodily movements produced in response to external stimuli and rewards—such the contingency between a rat’s pressing of a bar when a light is on and receipt of a food pellet reward—Dretske held that instrumental conditioning creates a link between a perceptual state triggered by the light and a motor state that controls bar-pressing movements, causing the rat to reliably press the bar more often in the future when the light is activated. Dretske says in this case that the neural state of detecting the light indicates that light is on, and when learning recruits this indicator to control bar-pressing movements, it bestows upon it the function of indicating this state of affairs going forward— a function which it retains even if it is later triggered in error, by something else (thus explaining misrepresentation as well).

This is a lovely way of weaving together causal origins, accuracy, and determinacy, and, like many other graduate students in the 1990s and 2000s, I got awfully excited about it when I first heard about it. Unfortunately, it still doesn’t work. There are lots of quibbles, but the main issue is that, despite appearances, it still has a hard time allowing for a representation to be both determinate and (later) tokened in error.

I present the argument as a dilemma on the term “indication”. Indication either requires perfect causal covariation, or something less. Consider the proverbial frog and its darting tongue; if the frog will also eat lead pellets flicked through its visual field, then its representation can only perfectly covary with some category that includes lead pellets, such as “small, dark, moving speck”. On this ascription, it looks impossible for the frog to ever make a mistake, because all and only small dark moving specks will ever trigger its tongue movements. If on the other hand indication during recruitment can be less than perfect, then we could say that the representation means something more intuitively satisfying like “fly”, but then we’ve lost the tight relationship between information theory and causal origins to settle indeterminacy, because there are lots of other candidate categories that the representation imperfectly indicated during learning (such as insect, food item, etc.).

This is all pretty familiar ground; what is less familiar is that there is a relatively unexplored “forward- looking” alternative that starts to look very good in light of this dilemma.

To my mind, the views that determine content by looking backward to causal history get into trouble precisely because they do not assign error a role in the content-determination process. Error on these views is a byproduct of representation; on backward-looking views, organisms can persist in error indefinitely despite having their noses rubbed in evidence of their mistake, like the frog that will go on eating BBs until its belly is full of lead.

Representational agents are not passive victims of error; in ideal circumstances, they should react to errors, specifically by revising their representational schemes to make those errors less likely in the future. Part of what it is to have a representation of X is to regard evidence that you’ve activated that representation in the absence of X as a mistake.

Content ascriptions should thus be grounded in the agent’s own epistemic capacities for revising its representations to better indicate their contents in response to evidence of representational error. Specifically, on my view, a representation means whatever it indicates at the end of its likeliest revision trajectory—a view that, not coincidentally, happens to fit very well with a family of “predictive processing” approaches to cognition that have recently achieved unprecedented success in cognitive science and artificial intelligence.

Want more?

Read the full article at https://journals.publishing.umich.edu/ergo/article/id/2238/.

About the author

Cameron Buckner is an Associate Professor in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Houston. His research primarily concerns philosophical issues which arise in the study of non-human minds, especially animal cognition and artificial intelligence. He just finished writing a book (forthcoming from OUP in Summer 2023) that uses empiricist philosophy of mind to understand recent advances in deep-neural-network-based artificial intelligence.