In this post, Naftali Weinberger discusses the article he recently published in Ergo. The full-length version of Naftali’s article can be found here.

After the first presidential debate between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, the consensus was that Clinton came out ahead, but that Trump exceeded expectations. Some sensed sexism, claiming: had Trump been a woman and Clinton a man, there’s no way observers would have thought the debate was even close, given the difference between the candidates’ policy backgrounds.

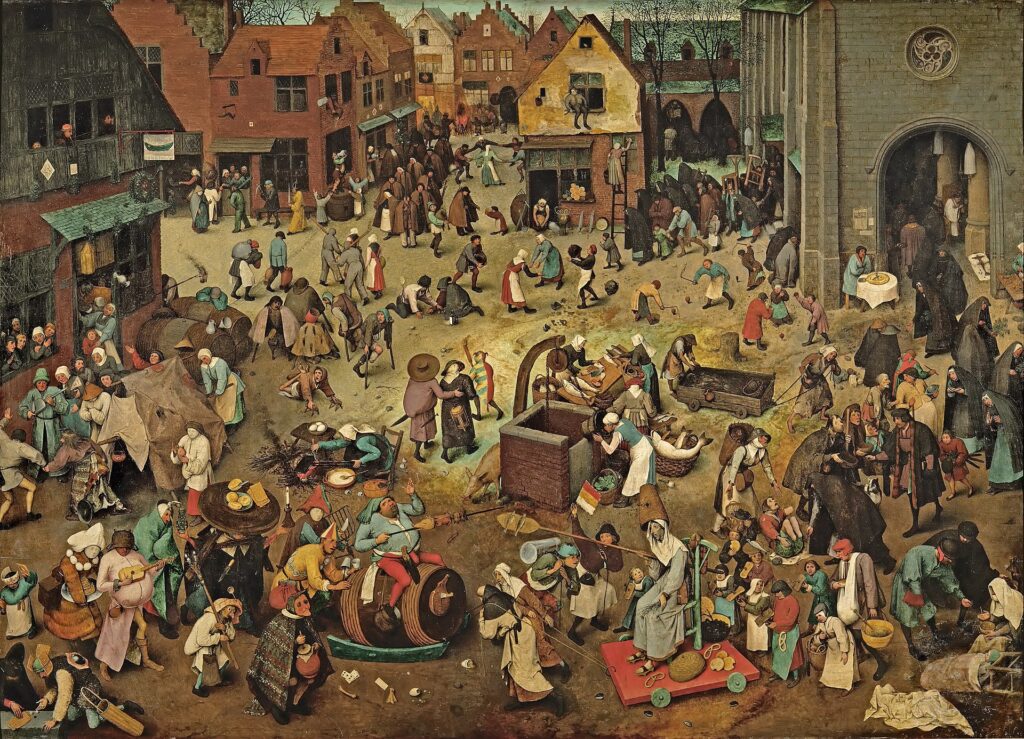

How could we test this hypothesis? Some professors at NYU staged a play with the candidates’ genders swapped. A female actor played Trump and imitated his words and gestures, and a male actor played Clinton. Afterwards, participants were given a questionnaire. Surprisingly, audience members disliked male Clinton more than observers of the initial debate disliked the original. “Why is he smiling so much?”, some asked. And: “isn’t he a bit effeminate?”

Does this show there was no sexism? Here we need to be careful. Smiling is not gender-neutral, since norms for how much people are expected to smile are themselves gendered. So perhaps we need to rerun the experiment, and change not just the actors’ genders, but also modify the gestures in gender-conforming ways such that male Clinton smiles less. The worry is that the list of required modifications might be open-ended. The public persona Clinton has developed over the last half century is not independent of her gender. If we start changing every feature that gets interpreted through a gendered lens, we may end up changing all of them.

This example illustrates how tricky it can be to test claims about the effects of demographic variables such as gender and race. I wrote “Signal Manipulation and the Causal Analysis of Racial Discrimination”, because I believe it is crucial to be able to empirically test at least some claims about discrimination, and that causal methods are necessary for doing so.

Studying racial discrimination requires one to bring together research from disparate academic areas. Whether race can be treated as a causal variable falls within causal inference. What race is, is a question for sociologists. Why we care specifically about discrimination against protected categories such as race is a matter for legal theorists and political philosophers.

Let’s start with whether race can be causal. Causal claims are typically tested by varying one factor while keeping others fixed. For instance, in a clinical trial one randomly assigns members to receive either the drug or the placebo. But does it make sense to vary just someone’s race or gender, while keeping everything else about them fixed?

This concern is often framed in terms of whether it is possible to experimentally manipulate race, and some claim that all causal variables must be potentially manipulable. I argue that manipulability is not the primary issue at stake in modeling discrimination. Rather, certain failures of manipulability point to a deeper problem in understanding race causally. Specifically, causal reasoning involves disentangling causal and merely evidential relevance: Does taking the drug promote recovery, or is it just that learning someone took the drug is evidence they were likely to recover (due to being healthier initially)? If one really could not change someone’s race without changing everything about them, the distinction between causal and evidential relevance would collapse.

We now turn to what race is. A key debate concerns whether it is biologically essential or socially constructed. Some think that race is non-manipulable only if it is understood biologically. Maya Sen and Omar Wasow argue that race is a socially constructed composite, and that even though one cannot intervene on the whole, one can manipulate components (e.g. dialect). Sen and Wasow do not theorize about the relationship between race and its components, and I believe this is by design. The underlying presupposition is that if race is constructed, it is nothing over and above the components through which it is socially mediated.

Yet race’s being socially constructed does not entail that it reduces to its social manifestations. To give Ron Mallon’s example: a dollar’s value is socially constructed, but this does not entail that there is nothing more to being a dollar than being perceived as one. Within our socially constructed value system, a molecule-for-molecule perfect counterfeit is still a counterfeit. The upshot of this is that even if race is a composite such that we can only manipulate particular components, it does not follow that race just is its components. The relationship between social construction and manipulability is more nuanced than has been presupposed.

Finally, how does the causal status of race connect to legal theories of discrimination? Discrimination law only makes sense given a distinction between discrimination on the basis of protected categories and mere arbitrary treatment. An employer who does not hire someone because the applicant simply annoys them might be irrational, but is not violating discrimination law. I argue that in order to distinguish between racial discrimination and arbitrary treatment, we need to be able to talk about whether race itself made a difference. This involves varying it independently of other factors and thus modeling it causally.

Where does this leave us with Clinton and Trump? I’d suggest that if we really can’t change Clinton’s perceived gender without changing everything about her, we cannot disentangle causal from evidential relevance, and causal reasoning does not apply. Fortunately, not all cases are like this. In audit studies, one can change a racially relevant cue (such as the name on a resume) to plausibly change only the racial information the employer receives. And this does not entail that race is only the name. Instead of asking whether race is a cause, we should ask when it is fruitful to model race causally, with a spectrum from cases like audit studies (in which it is) to cases like Clinton’s (in which it isn’t). And even in audit studies, treating race as separable is an idealization, since one does not model it in all of its sociological complexity. If what I argue in the article is correct, however, this modeling exercise is indispensable for legally analyzing discrimination and designing interventions to mitigate it.

Want more?

Read the full article at https://journals.publishing.umich.edu/ergo/article/id/2915/.

About the author

Naftali Weinberger is a scientific researcher at the Munich Center for Mathematical Philosophy. His work concerns the use of causal methodology to address foundational questions arising in the philosophy of science as well as questions arising in particular sciences, including: biology, psychometrics, neuroscience, and cognitive science. He has two primary research projects – one on causation in complex dynamical systems and another on the use of causal methods for the analysis of racial discrimination. He is currently trying to convince philosophers that causal representations are implicitly relative to a particular time-scale and that it is therefore crucial to pay attention to temporal dynamics when designing and evaluating policy interventions.