In this post, Ashley Atkins discusses the article she recently published in Ergo. The full-length version of Ashley’s article can be found here.

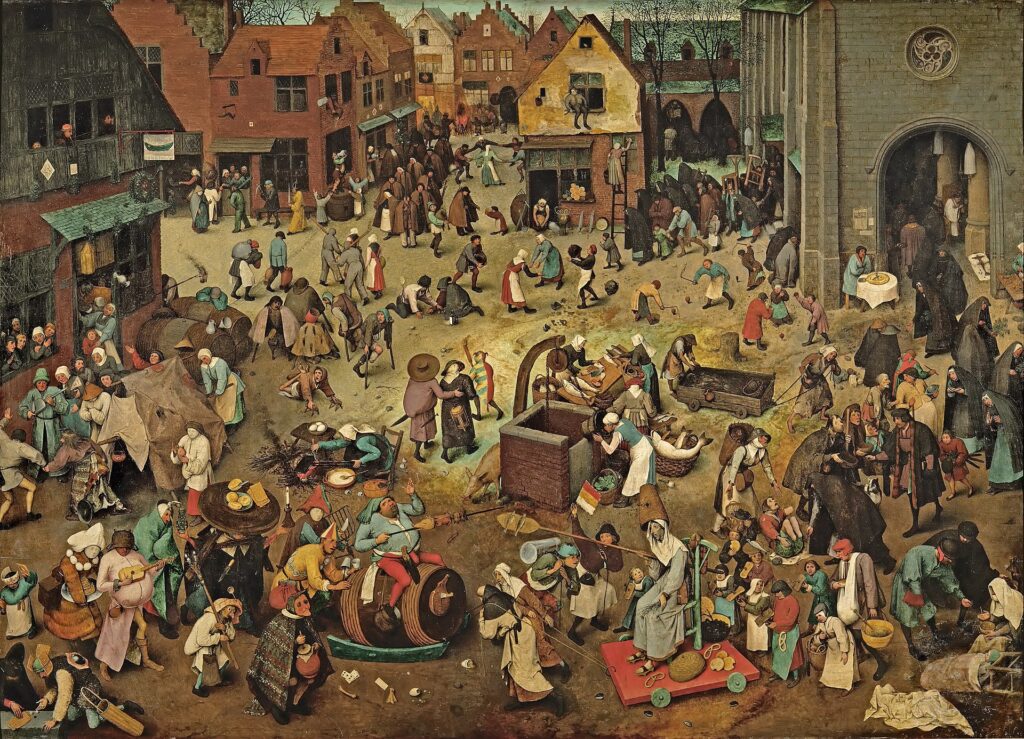

The exhibition of Dana Schutz’s Open Casket at the 2017 Whitney Biennial sparked immediate and passionate criticism: a protest was staged in front of the painting on its opening day; a public discussion of the controversy surrounding the painting was held by the Whitney during its exhibition; and sometime in between, a public letter was penned that called for the painting’s destruction.

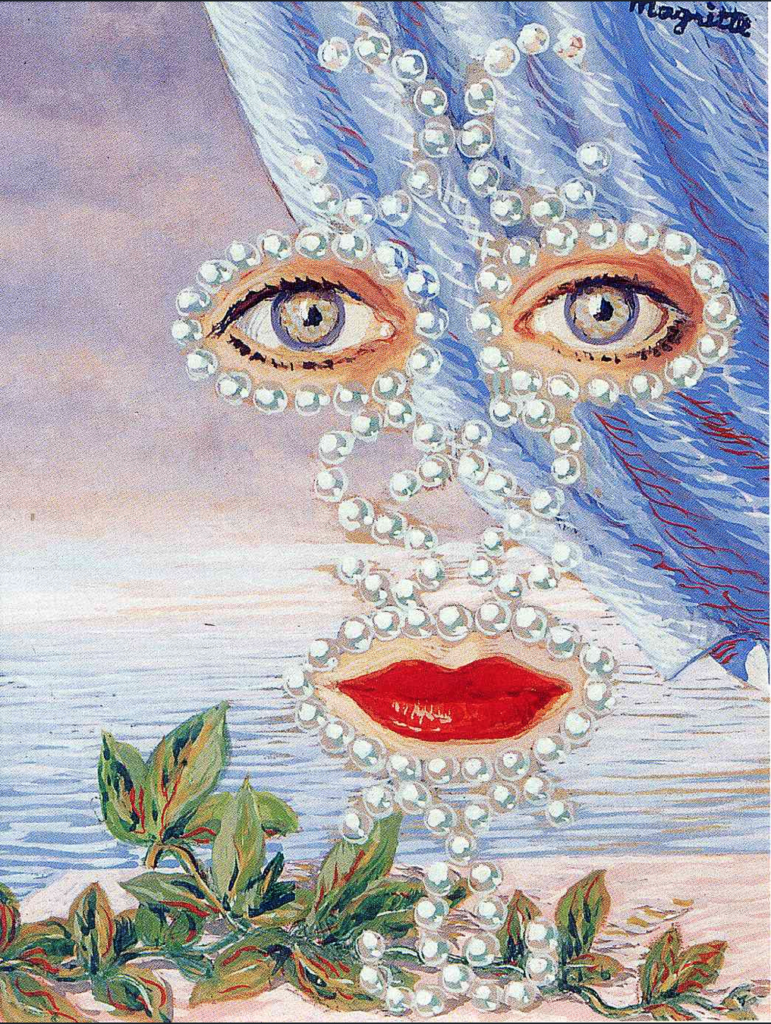

There are so few paintings of the dead in open casket that a painting of this kind was almost certain to capture people’s attention, even to shock. Helen Molesworth, a curator of contemporary art and former Chief Curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, articulates this shock in response to a recent exhibition of Alice Neel’s work, which included Dead Father (1946).

Though Molesworth “grew up in a tradition where you see dead people in coffin,” the act of making an image of this subject matter was felt to border on obscenity: “Nobody takes a picture of the dead person in a coffin, people don’t make paintings—oil paintings—of dead people in coffins. This is like […] almost taboo to me. Still, when I see that painting [Dead Father] I…I am a little shocked still.”

Obscenity was one of the charges presented against Open Casket (also an oil painting) but even so the feeling was that this bordered on something more sinister. Here we have a painting not of an intimate but of a stranger and, as Hannah Black—who led the call for its destruction—summed it up, a painting of a dead black boy by a white artist.

What propelled the controversy was the painting’s connection to its presumed—though not explicitly identified—subject, Emmett Till, a black teenager lynched in Mississippi in 1955, whose disfigured and badly decomposed body was laid in an open casket for the duration of a four-day public viewing at the insistence of his mother, Mamie Till-Mobley. What exactly, critics pointedly asked, is the artist’s relationship to this legacy? What does it mean to look at this painting?

Open Casket and the criticism surrounding it presents us with an opportunity to revisit this legacy and to examine, in particular, the significance of Mamie Till-Mobley’s public presentation of the body of her son, including her sanctioning of the publication of photographs of his body in casket, which continue to circulate. What can her actions mean to us today?

Schutz’s stated aims in painting Open Casket offer an illuminating starting point. Till-Mobley’s relationship to her son needed, in Schutz’s view, to be reflected in some way in this image; though the violence done to him was horrific and real and should be acknowledged as such—one of the reasons for its continuing political significance—the painting could not simply be grotesque (and I think we can see something in it of the tenderness that appears in Dead Father, what Fran Liebowitz unguardedly describes as beauty in her discussion of Neel’s painting). The image would also be, somehow, an American image.

We can find a basis for these ideas in Mamie Till-Mobley’s own reflections on these events, particularly in her declaration that all Americans needed to be impacted by the sight of the body as a whole so that they might together say what they had seen (Till-Mobley & Benson 2003: 140). As she reveals in her autobiography, Till-Mobley had herself studied the violence done to her son. She could describe it forensically, inch by inch, she tells us, but something other than this kind of engagement with the body of her son was intended by her invitation to Americans to look together and say what they saw. This was something she alone could not do. Americans also needed to see pictures of her son as he had been, she proposed, so that they could see what was lost to them.

It was through being initiated into rites of mourning, as we might put it, that Americans were to participate in this legacy. The most provocative aspect of Open Casket—what was experienced by critics as its intrusion into the mourning of others—is also, in my view, the central thread linking it to this legacy, namely, its engagement with Till-Mobley’s invitation to mourn her son’s legacy as an American one.

If this is right, why have critics neglected to consider that the painting might be a mournful one or to at least judge its failure in these terms?

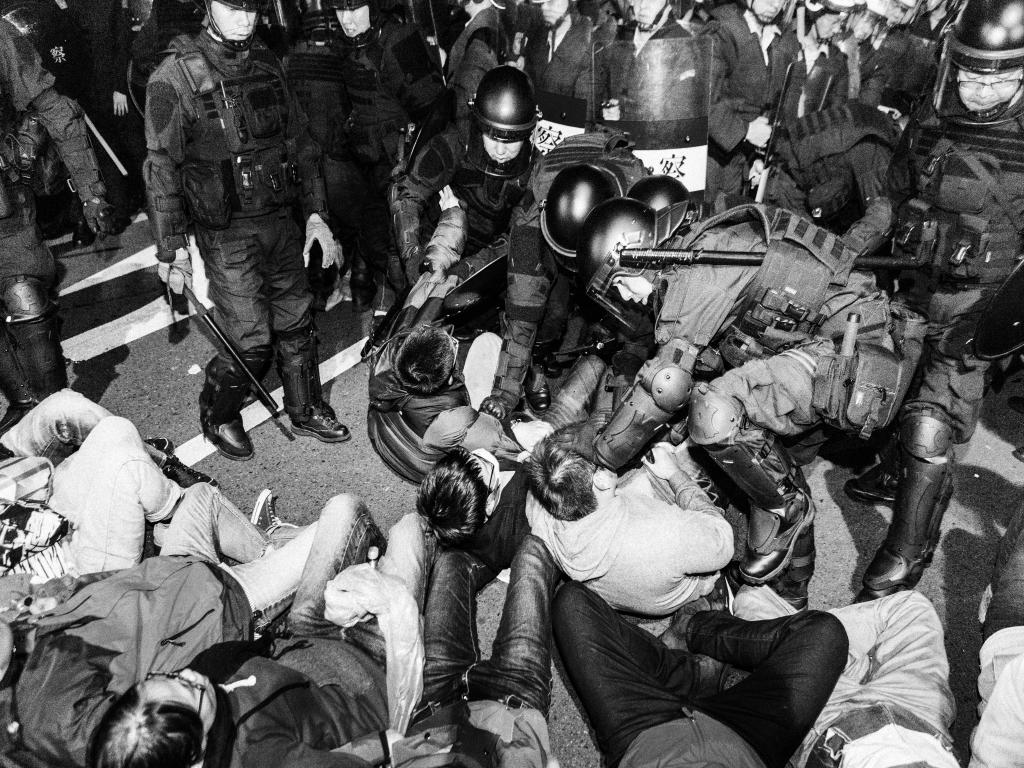

One important reason is that these critics do not understand this legacy in the terms that I set out; they would reject the idea that “racial losses” are to be mourned collectively. The critical reception of this legacy is a divided one. It assigns two complementary functions to the photographs of Emmett Till in casket: on the one hand, these photographs are understood to facilitate mourning (to provide shelter, warning, and inspiration) among those vulnerable to white violence and, on the other hand, these photographs circulate as evidence and are meant to expose those implicated in this violence (as Schutz was said to be through her painting). The aim of exposure can be seen in the rhetoric surrounding the violence associated with the iconography of Emmett Till’s death. The violence, critics insist, speaks for itself, bears its own witness, without any need for subjective response (of which mournfulness is a paradigm). It is on such grounds that Schutz’s painting is criticized for being too subjective.

But if this is right, why was there any need for Mobley to invite all Americans to look together? What use do we have for the idea that the loss of her son might be conceived of as a common loss?

It is tempting to understand Till-Mobley’s invitation to Americans within a tradition of political thought that sees democracy as requiring continual sacrifice and, relatedly, as requiring that citizens cultivate a capacity to mourn such losses (Allen 2004; McIvor 2016). Though this tradition is acutely aware of the ways in which the burdens of loss have historically been shifted onto to African Americans, among others, legacies of racial violence and loss engendered in this manner are thought to be no less collective for being borne inequitably. It is on these grounds that even these losses are to be mourned—that is, acknowledged as losses—by all citizens.

This tradition misses, however, the significance of and the challenge presented by Till-Mobley’s invitation. She did not assume that the loss of her son could already constitute a collective loss. She proposed that it be seen as such; i.e., that Americans come to think of themselves as people who had suffered this loss and needed, collectively, to put into words what it was and how it impacted them—an act of political re-envisioning so bold that its fulfillment would perhaps have been understood as a political refounding of the country. In this sense, we might see her as participating in the political lineage of Abraham Lincoln, who, it has been argued, also used a concrete occasion of mourning, in Gettysburg, to offer a vision of the country so bold in its re-envisioning that it has been conceptualized in these terms (Wills 1992; Nussbaum 2013).

On July 25, 2023, President Joe Biden signed a proclamation establishing the Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley National Monument in both Mississippi and Illinois (the family’s home state). The new national monument “will help tell the story of the events surrounding Emmett Till’s murder, their significance in the civil rights movement and American history, and the broader story of Black oppression, survival, and bravery in America.”

We can’t yet know how this story will be told. Will it present Emmett Till’s death as a loss to be mourned and, if so, by whom (what nation)? Will it present these events with tenderness, with beauty, which helps us to bear the ugliness of death and violence? Will Mamie Till-Mobley’s contribution to the civil rights movement be memorialized, as is standard, as helping “catalyze” this movement? This implies not only that her gesture was of great significance but that it was significant mainly for what followed, what would conventionally be thought of as properly political actions. Seeing Till-Mobley in this way would reflect the view of her contemporaries, among them powerful leaders in the NAACP who eventually publicly cut ties with her. In describing her grief as a catalyst and a benefit to later generations—the living rather than to the dead—they were making the point that grief was not itself of political significance, but rather a dangerous distraction from these other, properly political ends.

The question of what Mobley’s gesture can mean to us today will depend on many things, including our understanding of the prospects for a mournful politics.

Want more?

Read the full article at https://journals.publishing.umich.edu/ergo/article/id/2250/.

References

- Allen, Daniel (2004). Talking to Strangers: Anxieties of Citizenship Since Brown v. Board of Education. University of Chicago Press.

- McIvor, David W. (2016). Mourning in America: Race and the Politics of Loss. Cornell University Press.

- Till-Mobley, Mamie and Christopher Benson (2003). Death of Innocence: The Story of the Hate Crime That Changed America. Random House.

- Nussbaum, Martha (2013). Political Emotions: Why Love Matters for Justice. Harvard University Press.

- Wills, Gary (1992). Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words That Remade America. Simon and Schuster.

About the author

Ashley Atkins is an Associate Professor of Philosophy at Western Michigan University. She received an NEH Fellowship this year in support of a book project that examines grief through the lens of contemporary memoir. “Race and the Politics of Loss” is part of a series of papers exploring legacies of racial violence and loss in democratic politics.