In this post, Michael Cohen and Matteo Colombo discuss the article they recently published in Ergo. The full-length version of their article can be found here.

“the straight line… is the proper thing for the heart of a city. The curve is ruinous, difficult and dangerous; it is a paralyzing thing. The straight line enters into all human history, into all human aim, into every human act.”

Le Corbusier, “The City of Tomorrow“

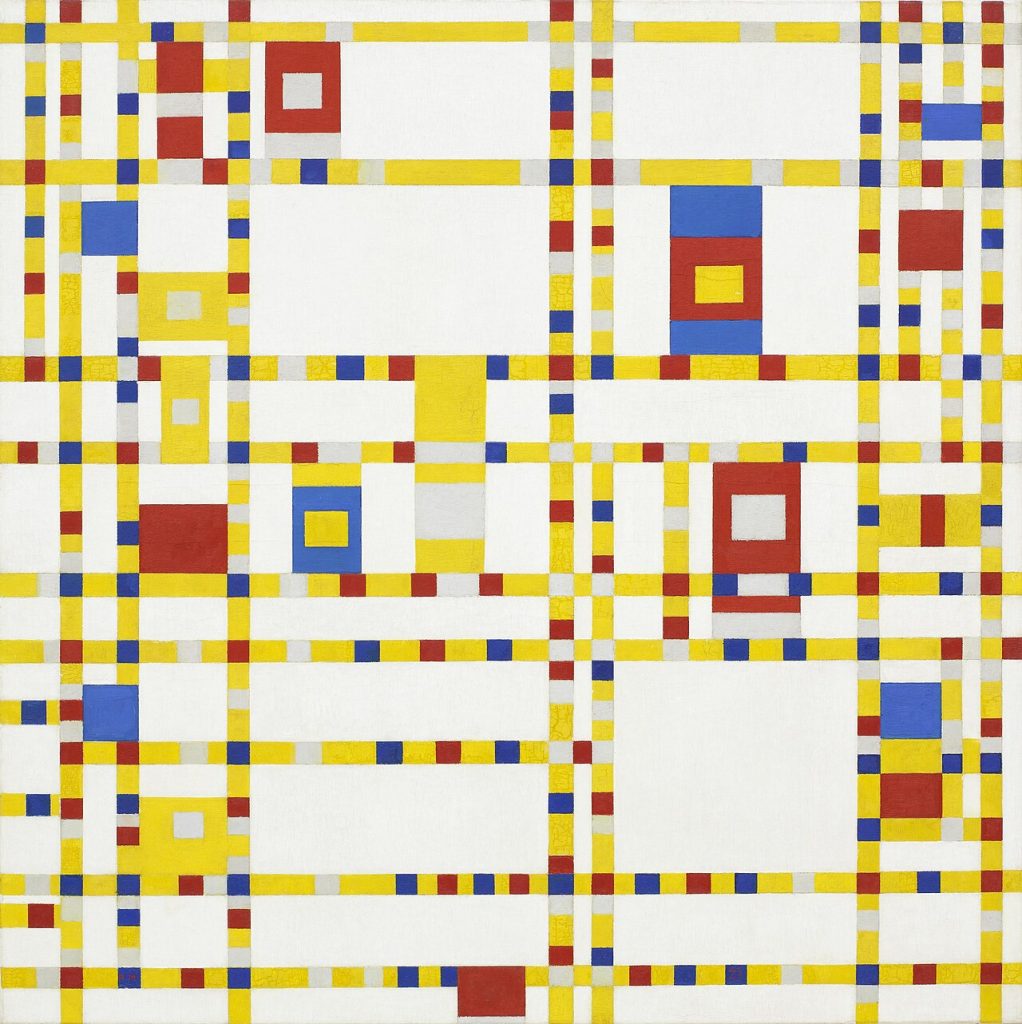

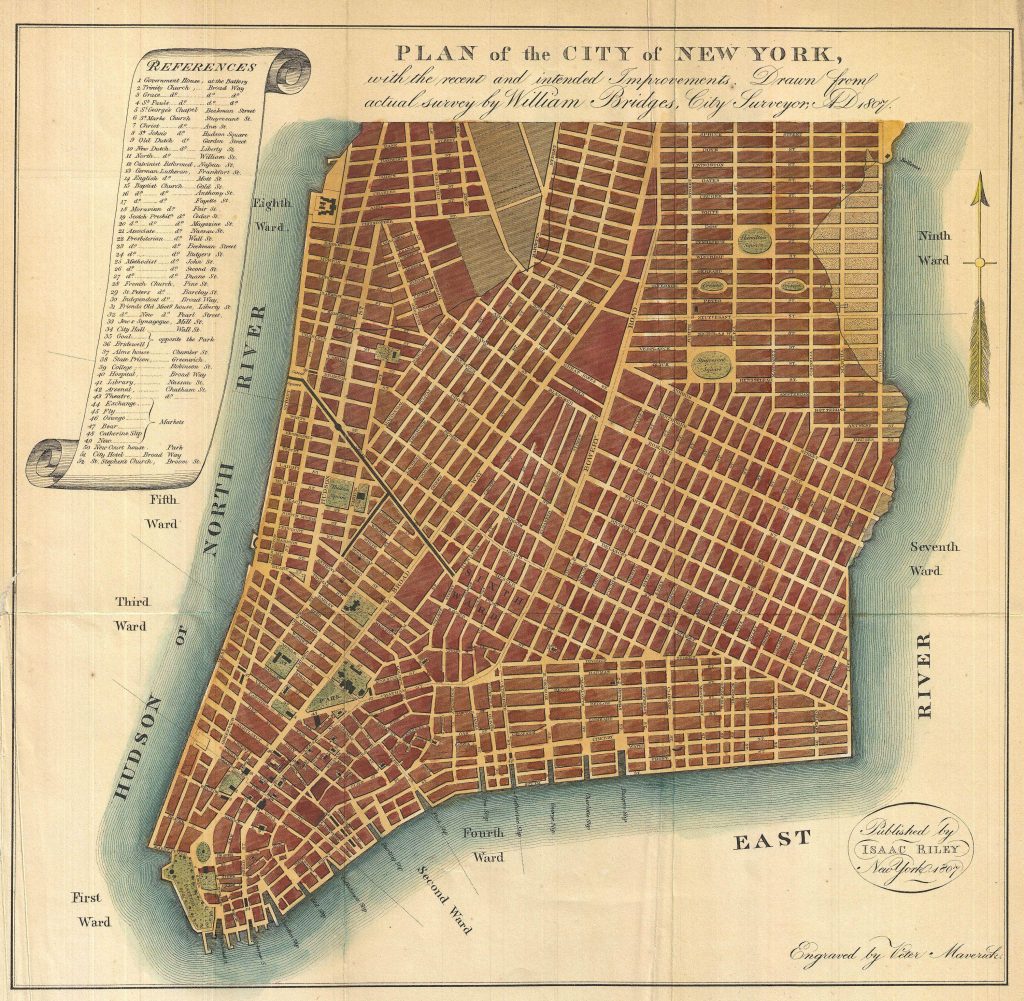

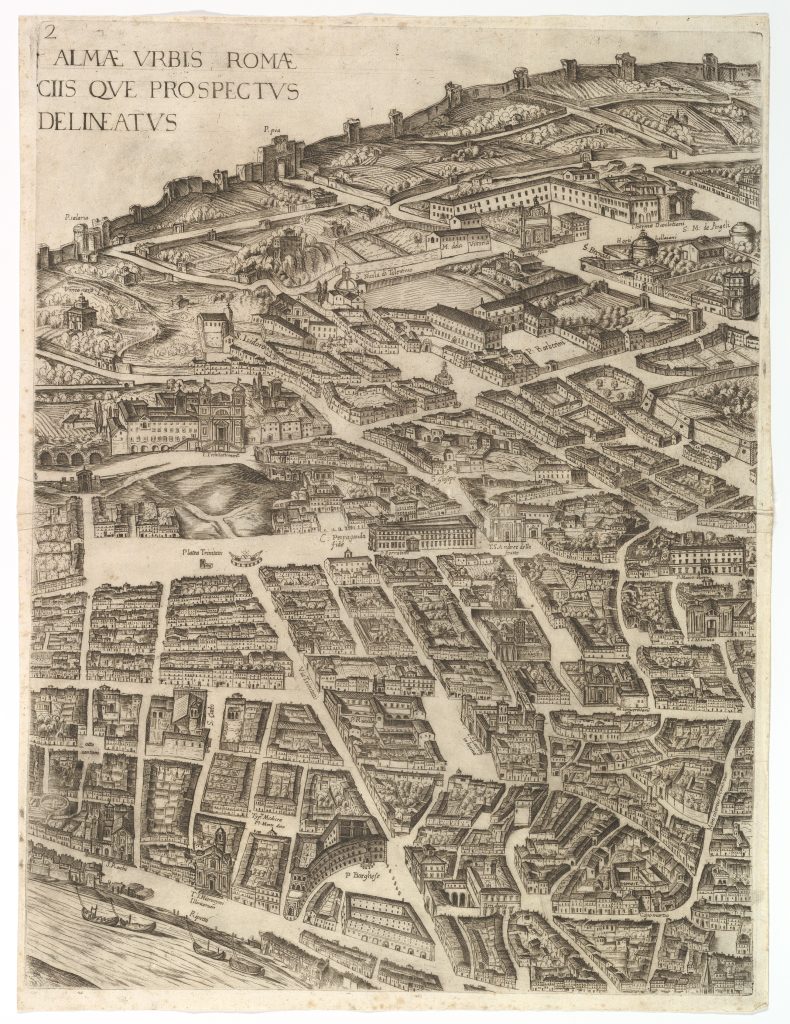

New York City has a regular grid plan. Like many other cities, the geometry of its environment consists of straight parallel paths and long streets running at right angles to each other. Cities such as Rome have a less regular plan, with many zigzagging short paths intersecting into curves with varying angles and no ordered distribution

Let’s imagine all features of New York City and Rome are similar, except their layout. That is, let’s imagine that Rome and New York City have similar extension, history, and climate, as well as similar distributions of wealth and income and of private and public areas, and so on. The agents in these two places are also similar, let’s suppose. They have similar political and religious beliefs; they all have basic capacities for perception, movement, and social learning; but they have different, personal preferences about fashion. Assuming all these imagined similarities, let’s now consider whether the differing geometry of their layouts will have an influence on the spread of a social norm of fashion among the dwellers in Rome and New York City about, say, the proper length of their trousers.

If spatial determinism is true—if it is true that “people’s agency and subjectivity are shaped and determined by the spaces they are in” (Kukla 2021, 13)—then this thought experiment should reveal that the different geometry of New York City and Rome will make this difference. But is spatial determinism true? Is there evidence that environments with different layouts can constrain social learning to produce universally shared norms of fashion in a population? Notice these types of questions apply at multiple spatial scales, also beyond city planning. For example, when choosing a new office layout, should you prefer an open space or a traditional layout with private offices? How will such choices influence your day-to-day behaviour? Will it make a difference to the emergence and spread of social norms in your department?

Philosophical utopias typically assume that spatial determinism is true, as they seek to promote conformity to a desired moral and political order partly based on the shape of the space the citizens of these utopias are in (Lisciandra & Colombo 2024). Spatial determinism is empirically vindicated in urban planning, where geometric features of a city can predict dwellers’ pattern of movement, the duration of their commutes, and the frequency of their encounters with random people (Hillier et al. 1986). Economic geographers have also demonstrated that the size of a city can predict its population density, commuting dynamics, quality of public service delivery, transit accessibility, economic growth, and environmental footprint (Batty 2008). This rich body of empirical evidence and theoretical insight supports spatial determinism, but does not clarify whether and how different city plans can shape the emergence and dynamics of a social norm such as a norm of fashion.

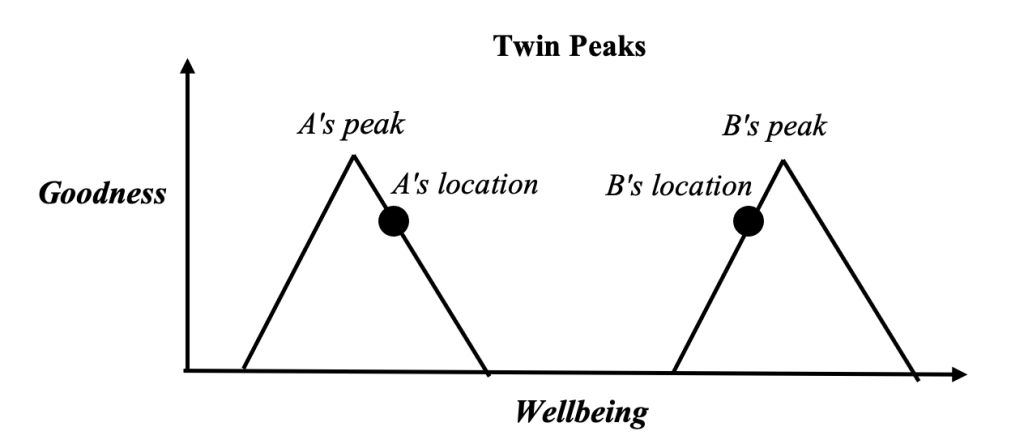

With our study, we wanted to contribute filling this gap, using agent-based modelling to explore how variation in the distribution of paths and barriers in an environment can constrain conformity-biased social learning to produce one, universally shared, descriptive norm in a population. Our simulations are highly idealized; but they show that a place with an irregular layout such as Rome can facilitate the emergence of multiple descriptive norms in a population, whereas a place with a regular grid plan such as New York City can constrain social learning to produce a behaviourally homogeneous population.

Because the agents in our simulations could learn from each other based on their degree of social sensitivity to the behaviours they could observe in other agents, an irregular space with barriers and paths, which limit who can observe whom, promoted diversity compared to a regular space with ample view. Moreover, our simulations suggested that population density, by itself, does not facilitate conformity. Rather, densely populated spaces facilitate conformity in regular environments, and diversity in irregular ones.

Our study complements existing work on the emergence of descriptive norms (Muldoon et al. 2014) and adds nuance to results about the impact of conformism on the epistemic dynamics of a group. Weatherall & O’Connor (2021) found that conformism can negatively influence the epistemic performance of a group. Fazelpour & Steel (2022) qualify this result by showing that demographic diversity can counteract the negative influence of conformism. By highlighting the role of the layout of the environment in constraining conformity-biased social learning, our own study indicates that conformism need not always have negative epistemic consequences for a group, since these consequences can be prevented with an appropriate design of the social learning environment.

Want more?

Read the full article at https://journals.publishing.umich.edu/ergo/article/id/8584/.

About the authors

Michael Cohen is Assistant Professor in the Department of Philosophy at Tilburg University, in the Netherlands. His research interests are in epistemology and formal philosophy, logic, AI, and philosophy of science. He comes from a city with with meandering and disorderly paths.

Matteo Colombo is Associate Professor in the Department of Philosophy at Tilburg University, in the Netherlands. His research interests are in the philosophy of mind and cognitive science, history and philosophy of science, and moral psychology. He comes from a city with less meandering, more orderly paths.