In this post, Alexandre Billon discusses his article recently published in Ergo. The full-length version of Alexandre’s article can be found here.

This chair, the moon, your toe, this hedgehog, and I, we all exist. But what does it mean for these things to exist? What does it mean for them to be real?

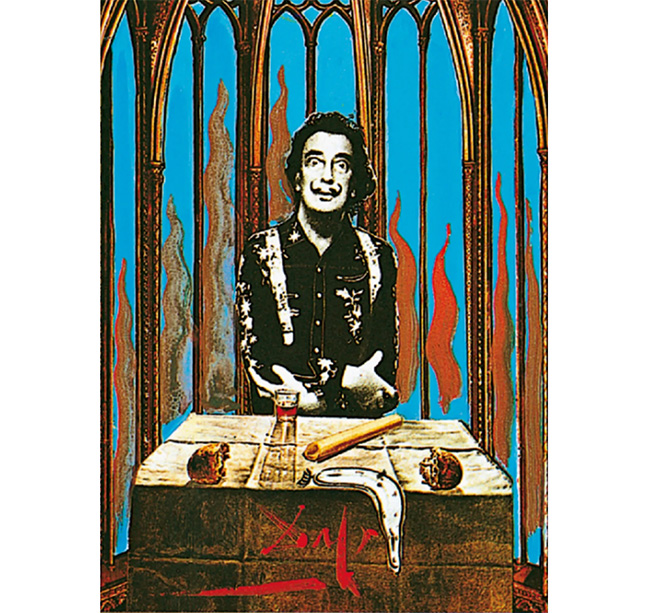

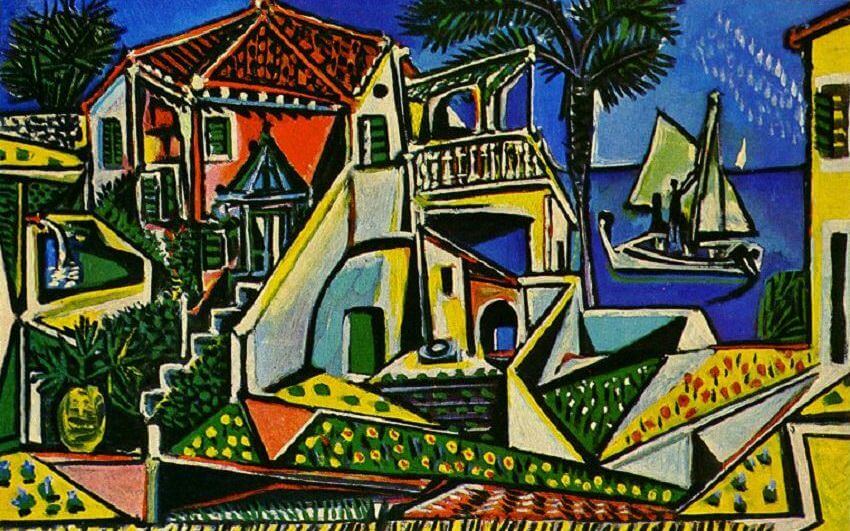

These questions may seem among the most abstract and sublime in all of philosophy, and certain professors, who dominated the French University when I was an undergraduate, elevated them to the status of disquieting metaphysical idols, burning up the gaze of the crowd while slowly revealing themselves, in the thick mists of the Black Forest, to the wise.

A simpler way of approaching these questions is to rely on the way existence spontaneously appears to us — let us call this the “sense of existence”. If I want to know what’s in front of me, I appeal to the verdict of my experience. Think, for example, of the proponents of the A-theory of time, according to which the present is a distinguished moment, so to speak, at the center of time. At the heart of their view is not a complex scientific theory, but rather the way the present appears to us.

The phenomenological tradition is famous for having sought to elucidate the nature of existence on the basis of the sense of existence. The problem is that, despite what a cursory glance might suggest, they don’t agree with each other at all. There is, for example, less common ground between Martin Heidegger’s and Michel Henry’s theses on this topic than between René Descartes’ and David Hume’s theses on the self.

This disagreement is not surprising. Look at a table in front of you and question your sense of the existence of this table. My expectation is that you will conclude that it is not obvious that the existence of the table, as opposed to the table itself, appears to you in any way whatsoever. The sense of existence, if it is there, is elusive, and many philosophers have abandoned the idea of relying on experience in order to investigate existence.

I think this abandonment is premature; there are ways of clarifying the sense of existence. To do this, we first need to be clear about various competing answers. This will ensure that we don’t passively accept the first proposal that comes along. Then, we need to use psychopathology to overcome some of the limitations of introspective analysis.

Let us first consider deflationary accounts of the sense of existence, which hold, with David Hume and Immanuel Kant, that our sense of the existence of a particular is nothing over and above our sense of that particular. For instance, they hold that, when we sense a cat, we don’t have an impression of the existence of the cat over and above our impression of the cat.

In contrast to deflationary accounts, there are several interesting non-deflationary theories. These can be traced back to the seminal work of the Encyclopedists (Turgot) and Ideologists (Condillac, Destutt de Tracy, Maine de Biran). They all admit of the existence of a kind of impression of existence, but they disagree on the content of this impression, which can be:

- an impression of the resistance of the real thing (Maine de Biran, Olivier Massin, Frédérique de Vignemont);

- an the impression of spatial depth of the real thing (Edmund Husserl);

- an impression that the real thing is an object of possible action, or “affordance” (Pierre Janet, Henri Bergson);

- an impression that the real thing is temporally present (Henri Bergson); or, finally,

- an impression that the real thing is in direct contact with us, or that we are acquainted with it (Turgot, Mohan Matten, perhaps Jérôme Dokic).

Which of these answers is best?

To evaluate these theories, we can try to determine why these impressions (of resistance, depth, temporally present character, etc.) merit the title of being impressions of reality rather than, say, redness or circularity.

The theorist of resistance can, for example, answer this question by invoking the idea that to exist is to have causal powers and that resistance is the mark of causal powers. The advocate of the Husserlian theory of depth can say that perceiving a thing as having depth is perceiving that it has hidden aspects, which do not reduce to the aspects we perceive, and that this is precisely what forms our sense of the reality of that thing. Similarly, the theory of temporally present character can be justified by claiming that the past and the future are unreal, whereas to be real, to exist, is to be now.

The acquaintance theorist, however, seems unable to produce a plausible answer. Unless they accept a kind of solipsistic idealism according to which what exists is what appears to them directly, it is difficult to see why such an appearance could be the mark of reality.

How else may we adjudicate which of these theories is best?

I suggest we look at a fairly common pathology: derealization (in the DSM-V tr ‘disorder of depersonalization and derealization’). Patients suffering from derealization seem to perceive the world exactly like us, except for existence. They see objects, their shapes and colors, but these objects seem unreal to them and, in extreme cases, literally non-existent.

This pathology is classically analyzed as involving an experiential gap. This suggests that deflationist answers are wrong: normally, there is in our experience something like an impression of existence in addition to our impressions of objects.

Moreover, derealization patients correctly perceive the resistance of things and, although they sometimes have disorders in the perception of the present, this is not always the case. This rules out the theory of resistance and the theory of the present.

In addition, by analyzing the subjective reports of patients, we find that they have no sensorimotor problems. On this basis, I argue that the theories of depth and affordances should also be ruled out.

How to characterize our sense of existence, then?

Karl Jaspers claims that this is a primitive impression, which we have no means of describing other than as an impression… of reality. I do not agree. There is, I think, a theory that is both plausible and compatible with the fact that people affected by derealization have normal sensorimotor abilities. This is the theory according to which our sense of existence is a sense of substantiality.

According to such theory, sensing that an object really exists is, roughly, sensing that it does not reduce to a bundle of properties but rather is a substrate, which carries and unifies these properties. This theory enables us to explain both that the reality of an object is normally perceived, and that the perception does not have any sensorimotor consequence.

David Chalmers briefly considers this theory in an article in the New York Times. According to him, the theory is however undermined by modern science.

Quantum wave functions with indeterminate values? That seems as ethereal and unsubstantial as virtual reality. But hey! We’re used to it.

If the structuralists – who claim that nothing has a real substrate beyond structure – or the digitalists – who claim that we live in a simulation and therefore nothing has a real substrate beyond digital structure – were right, then our sense of existence would indeed be massively erroneous. This would imply that patients who suffer from derealization see the world better than us.

However, pace Chalmers, modern scientific evidence per se does not compel us to endorse structuralism or digitalism, and if we reject both doctrines, we might take our sense of existence as a good guide for the metaphysics of reality. This sounds like a perfectly viable option to me.

Want more?

Read the full article at https://journals.publishing.umich.edu/ergo/article/id/3593/.

About the author

Alexandre Billon is Associate Professor of Philosophy at the University of Lille. Before that, he was a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Jean Nicod Institute. In his main works, he draws on the study of psychopathology to better understand the mind and the origin of our metaphysical intuitions.