In this post, Neil Levy discusses the article he recently published in Ergo. The full-length version of Neil’s article can be found here.

Much of my work has been devoted to arguing that bad believers – anti-vaxxers and climate change sceptics, say – are epistemically rational. That is, they respond to their evidence appropriately. They simply trust different sources of testimony to those of us who accept the official stories. This account has met with a variety of objections, but there’s one in particular that I concede my account can’t handle: the objection from the incredulous stare. There are bad beliefs that people just can’t accept on a rational basis; not in this century, with access to the information we all have available and in the face of easily assessed evidence.

Think of those people who purport to believe that reptilian shape-shifters occupy central positions of power in the world, including among their ranks US presidents, British and Canadian prime ministers, and the House of Windsor. This theory has many thousands of adherents and David Icke, its principal proponent, speaks to crowds numbering in their thousands. How can anyone seriously believe that?

While there may be some few people who are true believers, I suspect that they are a small proportion of the people who say they believe that King Charles is a reptilian, or those who say they believe the Earth is flat. In addition to the true believers, there are many trolls and shmelievers.

True believers are people genuinely trying to proportion their belief that the Earth is flat to their evidence who end up believing that the Earth is flat. They probably exist, but they are unusual. Trolls are people who don’t believe that the Earth is flat but enjoy the reaction they get when they say that they believe that the Earth is flat. Shmelievers are people who don’t believe that the Earth is flat but take themselves to believe it.

There’s good evidence that a significant proportion of respondents to polls and participants in research are trolls. Consider the claim that a significant number of people drank bleach to combat COVID-19. The CDC’s research found that 4% of respondents were drinking bleach (allegedly following Trump’s advice). Leib Litman and colleagues replicated the CDC study with a larger sample. But once the people who reported accidentally drinking a cleaning product or accidentally answering ‘yes’ to the question were eliminated, 100% of those who reported drinking or gargling with bleach or another household cleaner were ‘problematic respondents’. They also reported incredible demographics, or that they had never used the internet in their lives (the study was online), or that they had previously suffered a fatal heart attack. They’re trolls, reporting beliefs they don’t hold for the lulz.

Expressive responders also count as trolls on this taxonomy, though their motivation seems to be to express or to signal support for their side by insincere report. For example, the 15% of Trump supporters who reported believing that a photo of his inauguration showed more people than did a photo of the Obama inauguration count as trolls; it’s not plausible that they really thought the photo showed more people.

While there is direct evidence for the existence of trolls, the existence of shmelievers must be inferred. We have grounds for thinking that some people who report believing incredible claims, like the flat Earth theory, are sincere. Sometimes they come to reject the belief but report they were sincere at the time. Yet they don’t seem to be believers either. They don’t act consistently with the theory, for instance. Hugo Mercier points to the many people who claimed to believe that Jewish shopkeepers were kidnapping gentile girls in the town of Orleans in the late ‘60s. At the height of the rumor, some people stopped and stared at the supposedly offending shops – hardly the response called for by true belief.

Shmeliefs can also be distinguished from genuine beliefs by the kind of evidence that shmelievers cite for them. True believers are discerning in what evidence they accept; shmelievers are not. Recall the kinds of evidence cited during the pandemic for the claim that the whole thing was a nefarious plot: the fact that ‘delta omicron’ is an anagram of ‘media control’ or claims that movies like I Am Legend show the dangers of the vaccine. When people cite evidence like that, they demonstrate that they aren’t really concerned with the truth of their claims.

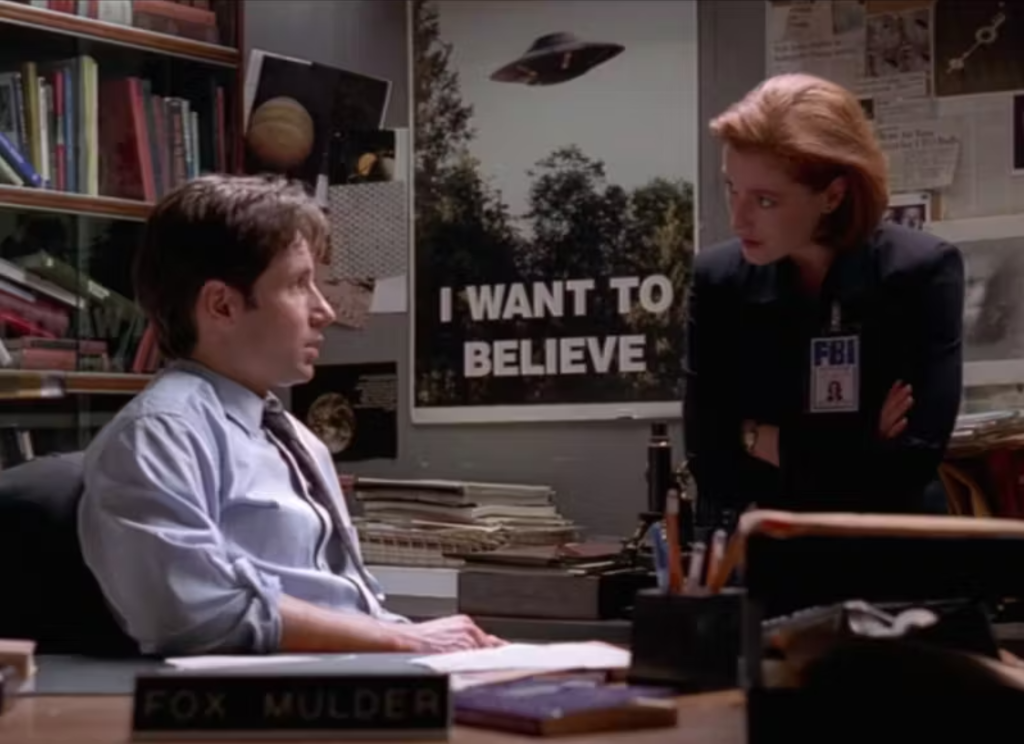

How can someone take themselves to believe something they don’t believe? Citing anagrams and movie stills as evidence is a playful approach to offering support, and I think shmelievers are engaged in a sort of imaginative game. Being a believer is akin to becoming absorbed in a fiction. Conspiracy theories are, after all, fun; it’s easy to get absorbed in the conspiratorial or paranormal enchanted worlds they offer us. The main difference between me watching the X-Files and the conspiracy theorist who takes themselves to believe that the US is really concealing the bodies of aliens from a UFO that crashed at Roswell is that I know it’s a fiction.

How do shmelievers lose track of the fact that they’re playing ‘conspiracy theory’? At least part of the explanation is that shmeliefs often receive social support: the shmeliever identifies with people who share the fantasy, while people that push back against it are neither trusted by the shmeliever nor apt to engage them in a way that encourages dialogue. Moreover, the world doesn’t push back against the shmelief; the shmelief predicts the evidence that might be cited against it. This is known as the ‘self-sealing quality’ of conspiracy theories: any attempt to dispel the theory can be interpreted as further proof of the conspiracy.

If bizarre claims are believed less often than we might think and have few consequences for behavior, what harm do they do? I suspect that shmeliefs are often supported by and help to sustain genuine beliefs (that the government doesn’t care about people like me, for example). However, shmeliefs prevent these genuine beliefs from coming clearly into view, either for the shmeliever or for those around them. To that extent, they undermine dialogue and side track debates down unproductive alleys. These effects might be sought: those who want to stymie debate have an interest in the promotion of shmeliefs.

Want more?

Read the full article at https://journals.publishing.umich.edu/ergo/article/id/6158/.

About the author

Neil Levy is professor of philosophy at Macquarie University (Sydney) and a senior research fellow at the Uehiro Oxford Institute, University of Oxford. He has published widely in philosophy on a variety of topics, with an emphasis recently on the rationality of belief.