In this post, Thomas Brouwer discusses the article he recently published in Ergo. The full-length version of Thomas’ article can be found here.

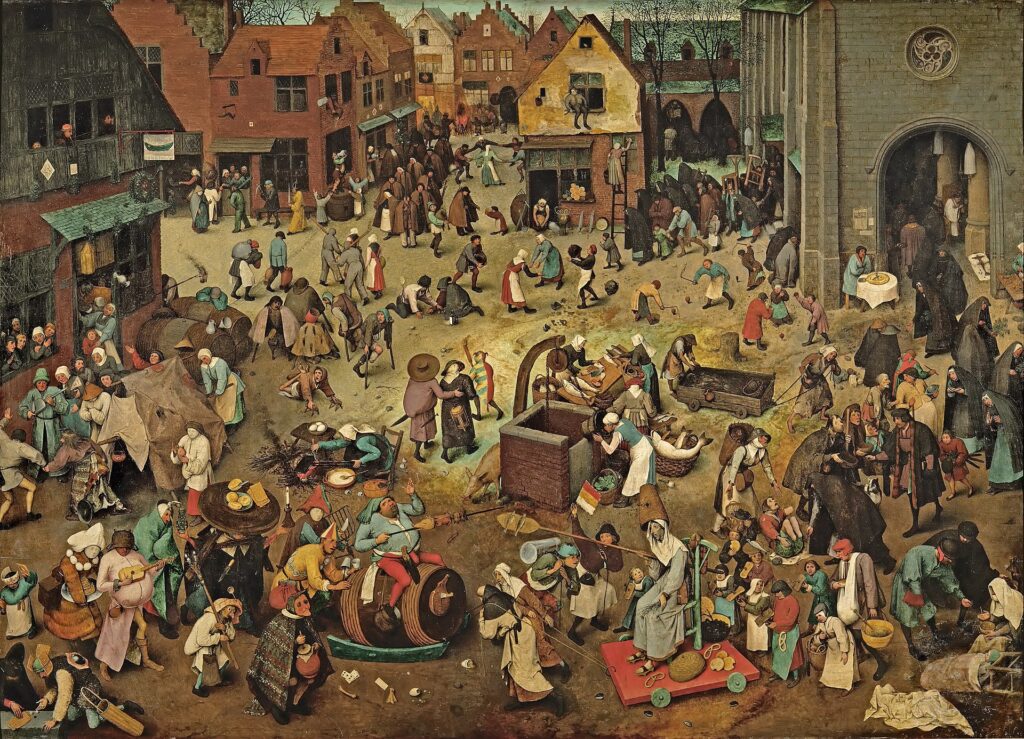

Social reality consists in all the things that we humans layer onto the world by means of our social interactions. It includes social norms, customs, fashions, conventions and laws; organizations such as businesses and universities; social groupings like genders, sub-cultures and socio-economic classes; artifacts such as tools, artworks, currencies, and buildings; languages, cuisines, and religions.

The elements that make up social reality come about in various ways, some the products of conscious design, some arising spontaneously out of social interactions. In neither case is quality of construction guaranteed. We are all familiar with the variety of defects social institutions can exhibit. They can be wasteful, unjust, fragile, and easily subverted; they can prove inflexible when circumstances change; they can be opaque. The focus of my investigation is a further, less familiar type of defect: inconsistency.

Inconsistency is a logical notion. A set of statements is inconsistent when you can logically derive a contradiction from it. In other words, when it implies that something is the case and also not the case. Since it is hard to act effectively on contradictory information, inconsistency can be practically problematic; but inconsistency is also tricky philosophically. In many systems of logic – particularly classical logic and intuitionistic logic – contradictions have the troubling property that they entail everything. Once a body of claims implies that something both is and is not the case, it also implies any other claim.

Philosophers have often taken this to motivate a metaphysical claim, namely that the world itself has to be consistent. If you could write down everything true about it, your list would not contain any contradictions. The idea is simple: if there were inconsistencies among the facts, and inconsistencies entail everything, then literally everything would be the case. The moon would be made of cheese and pigs would fly. So, if the world were inconsistent, you’d think we’d have noticed.

Since the latter half of the twentieth century, however, logicians have developed alternative logics which don’t ‘explode’ (as logicians like to put it) in the face of inconsistency. This logical innovation has spurred a philosophical one: some philosophers have been exploring the view, once regarded as a non-starter, that the world can sometimes be inconsistent. This view is called dialetheism, and it comes in different flavours, depending on where in the world you suspect inconsistency. Often, arguments for dialetheism focus on logical paradoxes such as the Liar paradox (‘this sentence is false’), for which satisfying consistent solutions are hard to achieve.

The social world has so far received little attention from dialetheists, with the exception of Priest (1987, ch. 13) and Bolton & Cull (2020). Yet it might be one of the likeliest places to find inconsistency. Here is why.

One major way in which we shape social reality is by laying down conditions for certain social states of affairs. For example, by developing shared expectations and aesthetic reactions, we make it the case that if you put on a certain cut of trousers, you will be unfashionable; by passing a criminal law, we make it the case that if you commit a certain act, you will be a criminal. The mechanics of laying down conditions – or, as we might call it, social construction – have been variously described by social metaphysicians. In my article, I build particularly on Brian Epstein’s (2015) theory. An appealing feature of his theory, as I see it, is that it allows for a realistic amount of disorderliness in the construction of social reality. It allows that the different elements of social reality are constructed through disparate processes, which may involve entirely different people with a variety of purposes, and it allows that the people involved in these processes may lack insight into or substantive control over what they are doing. Social reality is just what ends up emerging out of this dispersed, uncoordinated and often confused activity.

One among many things that can go awry, amid this activity, is that we can end up laying down a condition for something to be the case, and also a condition for it not to be the case, in such a way that these conditions are jointly satisfiable. This is not the sort of thing that we would do if we were clear-eyed and coordinated, but we are not always clear-eyed and coordinated.

Complex regulations are a good case to think about. Consider for instance the intricacies of a tax code, and the scenarios that it yields for devising and revising criteria in muddled ways over time. It is not so strange to think that a person can end up both qualifying and not qualifying for some tax break. Or think about games: the philosopher Ted Cohen argued in 1990 that under the then-current rules of baseball, if a runner hit the base at the same time as being tagged, they were in and also out (and therefore not in). Such scenarios are not surprising on the kind of picture of social reality which I sketched. On that picture, consistency in the social world is something that we would have to achieve through care and coordination, not something that is already built in.

Philosophically, this is just an opening move. One might admit that yes, we can screw up our social institutions in such a way that they appear to produce contradictions. But are these really contradictions, or will a more subtle metaphysics reveal that these contradictions are mere surface appearances? I think many philosophers would want to say so. In my article, I develop and consider several cases against social inconsistency on their behalf. Some are more promising than others – but my ultimate conclusion is that we should remain open to social inconsistency.

If this is right, what follows? First off, unless we also want to think that absolutely everything is true, we should embrace some form of paraconsistent logic. But there are further consequences to think about as well. Social facts often have normative import; if you fall in a certain tax bracket, for example, then you should pay that much tax. If there are social inconsistencies, however, some of them could generate dilemmas: situations in which you ought to do something, but you also ought not do it. Many philosophers think dilemmas cannot happen, because of the principle that ought implies can. Social inconsistency might, among other things, give us a reason to re-examine that commitment.

Want more?

Read the full article at https://journals.publishing.umich.edu/ergo/article/id/2258/

References

- Bolton, Emma and Matthew J. Cull (2020). “Contradiction Club: Dialetheism and the Social World”. Journal of Social Ontology 5(2), pp. 169–80.

- Cohen, Ted (1990). “There Are No Ties at First Base”. Yale Review 79(2), pp. 314-22. Reprinted in Eric Bronson (ed.), Baseball and Philosophy (2004, pp. 73-86). McLean: Open Court Books.

- Epstein, Brian (2015). The Ant Trap: Rebuilding the Foundations of the Social Sciences. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Priest, Graham (1987/2006). In Contradiction (second edition). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

About the author

Thomas Brouwer is a Research Fellow and Research Development Assistant at the University of Leeds. He studied at the University of Leiden, in the Netherlands, did his PhD at Leeds, and worked at the University of Aberdeen before returning to Leeds. After working initially in metaphysics and the philosophy of logic, he now works mainly in social ontology. He is especially interested in the metaphysics of social facts, the actions and attitudes of groups, and the mechanics of social norms and conventions.