In this post, Bryan Pickel and Brian Rabern discuss the article they recently published in Ergo. The full-length version of their article can be found here.

A central achievement of early analytic philosophy was the development of a formal language capable of representing the logic of quantifiers. It is widely accepted that the key advances emerged in the late nineteenth century with Gottlob Frege’s Begriffschrift. According to Dummett,

“[Frege] resolved, for the first time in the whole history of logic, the problem which had foiled the most penetrating minds that had given their attention to the subject.” (Dummett 1973: 8)

However, the standard expression of this achievement came in the 1930s with Alfred Tarski, albeit with subtle and important adjustments. Tarski introduced a language that regiments quantified phrases found in natural or scientific languages, where the truth conditions of any sentence can be specified in terms of meanings assigned to simpler expressions from which it is derived.

Tarski’s framework serves as the lingua franca of analytic philosophy and allied disciplines, including foundational mathematics, computer science, and linguistic semantics. It forms the basis of the predicate logic conventionally taught in introductory logic courses – recognizable by its distinctive symbols such as inverted “A’s” and backward “E’s,” truth-functions, predicates, names, and variables.

This formalism proves indispensable for tasks such as expressing the Peano Axioms, elucidating the truth-conditional ambiguity of statements like “Every linguist saw a philosopher,” or articulating metaphysical relationships between parts and wholes. Additionally, its computationally more manageable fragments have found applications in semantic web technologies and artificial intelligence.

Yet, from the outset there was dissatisfaction with Tarski’s methods. To see where the dissatisfaction originates first, consider the non-quantified fragment of the language. For this fragment, the truth conditions of any complex sentence can be specified in terms of the truth conditions of its simpler sentences, and the truth conditions of any simple sentence, in turn, can be specified in terms of the referents of its parts. For example, the sentence ‘Hazel saw Annabel and Annabel waved’ is true if and only if its component sentences ‘Hazel saw Annabel’ and ‘Annabel waved’ are both true. ‘Hazel saw Annabel’ is true if the referents of ‘Hazel’ and ‘Annabel’ stand in the seeing relation. ‘Annabel waved’ is true if the referent of ‘Annabel’ waved. For this fragment, then, truth and reference can be considered central to semantic theory.

This feature can’t be maintained for the full language, however. To regiment quantifiers, Tarksi introduced open sentences and variables, effectively displacing truth and reference with “satisfaction by an assignment” and “value under an assignment”. Consider for instance a sentence such as ‘Hazel saw someone who waved’. A broadly Tarskian analysis would be this: ‘there is an x such that: Hazel saw x and x waved’. For Tarski, variables do not refer absolutely, but only relative to an assignment. We can speak of the variable x as being assigned to different individuals: to Annabel or to Hazel. Similarly, an open sentence such as ‘Hazel saw x’ or ‘x waved’ is not true or false, but only true or false relative to an assignment of values to its variables.

This aspect of Tarski’s approach is the root cause of dissatisfaction, yet it constitutes his unique method for resolving “the problem” – i.e., the problem of multiple generality that Frege had previously solved. Tarski used the additional structure to explain the truth conditions of multiply quantified sentences such as `Everyone saw someone who waved’, or `For every y, there is an x such that: y saw x and x waved’. The overall sentence is true if for every assignment of values to ‘y’, there is an assignment of values to both ‘y’ and ‘x’ such that ‘y saw x’ and ‘x waved’ are both true on that assignment.

Tarksi’s theory is formally elegant, but its foundational assumptions are disputed. This has prompted philosophers to revisit Frege’s earlier approach to quantification.

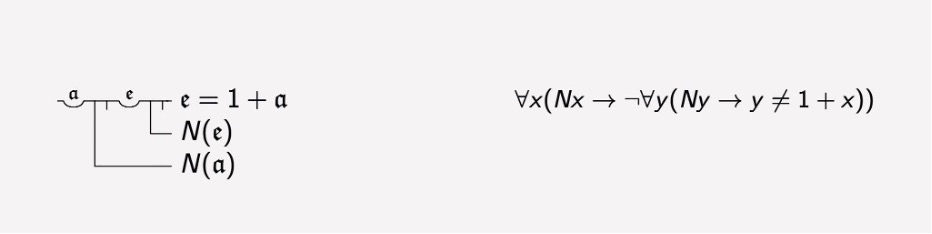

According to Frege, a “variable” is not even an expression of the language but instead a typographic aspect of a distributed quantifier sign. So Frege would think of a sentence such as ‘there is an x such that: Hazel saw x and x waved’ as divisible into two parts:

- there is an x such that: … x….

- Hazel saw … and … waved

Frege would say that expression (ii) is a predicate that is true or false of individuals depending on whether Hazel saw them and they waved. For Frege, this predicate is derived by starting with a full sentence such as ‘Hazel saw Annabel and Annabel waved’ and removing the name ‘Annabel’. In this way, Frege seems to give a semantics for quantification that more naturally extends the non-quantified portion of the language. As Evans says:

[T]he Fregean theory with its direct recursion on truth is very much simpler and smoother than the Tarskian alternative…. But its interest does not stem from this, but rather from examination at a more philosophical level. It seems to me that serious exception can be taken to the Tarskian theory on the ground that it loses sight of, or takes no account of, the centrality of sentences (and of truth) in the theory of meaning. (Evans 1977: 476)

In short: Frege did it first, and Frege did it better.

Our paper “Against Fregean Quantification” takes a closer look at these claims. We identify three features in which the Fregean approach has been held to make an advance on Tarski: it treats quantifiers as predicates of predicates, the basis of the recursion includes only names and predicates, and the complex predicates do not contain variable markers.

However, we show that in each case, the Fregean approach must similarly abandon the centrality of truth and reference to its semantic theory. Most surprisingly, we show that rather than extending the semantics of the non-quantified portion of the language, the Fregean turns ordinary proper names into variable-like expressions. In doing so, Frege leads to a typographic variant of the most radical of Tarskian views: variabilism, the view that names should be modeled as Tarskian variables.

Want more?

Read the full article at https://journals.publishing.umich.edu/ergo/article/id/2906/.

References

- Dummett, Michael. (1973). Frege: Philosophy of Language. London: Gerald Duckworth.

- Evans, Gareth. (1977). “Pronouns, Quantifiers, and Relative Clauses (I)”. Canadian Journal of Philosophy 7(3): 467–536.

- Frege, Gottlob. (1879). Begriffsschrift: Eine der arithmetischen nachgebildete Formelsprache des reinen Denkens. Halle a.d.S.

- Tarski, Alfred. (1935). “The Concept of Truth in Formalized Languages”. In Logic, Semantics, Metamathematics (1956): 152–278 . Clarendon Press.

About the authors

Bryan Pickel is Senior Lecturer in Philosophy at the University of Glasgow. He received his PhD from the University of Texas at Austin. His main areas of research are metaphysics, the philosophy of language, and the history of analytic philosophy.

Brian Rabern is Reader at the School of Philosophy, Psychology, and Language Sciences at the University of Edinburgh. Additionally, he serves as a software engineer at GraphFm. He received his PhD in Philosophy from the Australian National University. His main areas of research are the philosophy of language and logic.