In this post, Christopher Frugé discusses the article he recently published in Ergo. The full-length version of his article can be found here.

Grounding is the generation of the less fundamental from the more fundamental. The fact that Houston is a city is not a fundamental aspect of reality. Rather, it’s grounded in facts about people and, ultimately, fundamental physics.

What is the status of grounding itself? Most theorists of ground think that grounding is non-fundamental and so must itself be grounded. Yet, if grounding is always grounded, then every grounding fact generates an infinite regress of the grounding of grounding facts, where each grounding fact needs to be grounded in turn. I argue that this regress is vicious, and so some grounding facts must be fundamental.

Grounding theorists take grounding to be grounded because it seems to follow from two principles about fundamentality. Purity says that fundamental facts can’t contain any non-fundamental facts. Completeness says that the fundamental facts generate all the non-fundamental facts. The idea behind purity is that the fundamental is supposed to be ‘pure’ of the non-fundamental. There can’t be any chairs alongside quarks at the most basic level of reality. Completeness stems from the thought that the fundamental is ‘enough’ to generate the rest of reality. Once the base layer has been put in place, then it produces everything else.

These principles are plausible, but they lead to regress. For example, the fact that Houston is a city is grounded in certain fundamental physical facts. By the standard construal of purity, this grounding fact is non-fundamental, since it ‘contains’ a non-fundamental element: the fact that Houston is a city. But by completeness, non-fundamental facts must be grounded, so this grounding fact must be grounded. But then this grounding fact must be grounded for the same reason, and so on forever.

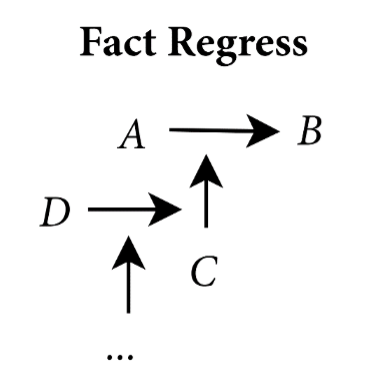

We have what’s called the fact regress:

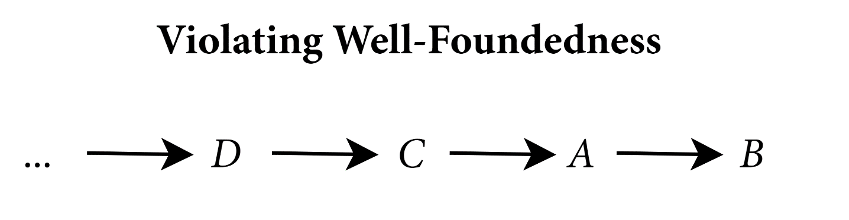

The standard take among grounding theorists is that the regress isn’t vicious, just a surprising discovery. This is because it doesn’t violate the well-foundedness of grounding. Well-foundedness requires that at some point each path of A grounds B and C grounds A and D grounds C… must come to an end.

The fact regress doesn’t violate well-foundedness, because each grounding fact can ground out in something fundamental. It’s just that each grounding fact needs to be grounded. Consider a case where A is fundamental and grounds B, but this grounding fact is grounded in a fundamental C. And that grounding fact is grounded in a fundamental D and so on. This satisfies well-foundedness but is an instance of the fact regress.

Nonetheless, I claim that the fact regress is still vicious. This is because what’s grounded doesn’t merely depend on its ground but also depends on the grounds of its grounding fact – and on the grounds of each grounding fact in the path of grounding of grounding. Call this connection dependence.

Why is connection dependence a genuine form of dependence? Suppose that A grounds B, where B isn’t grounded in anything else. But say that C grounds that A grounds B, where A grounds B isn’t grounded in anything else. Then, B depends not just on A but also on C. If C were removed, then A wouldn’t ground B. So then B would not be generated by anything and so would not come into being. For example, if a collection of particles ground the composite whole of those particles only via a composition operation grounding this grounding fact, then if, perhaps counterpossibly, there were no composition operation then those particles would not ground that whole. Similar reasoning applies at each step in the path of grounding of grounding.

So, then, the fact regress is bad for the same reason that violations of well-foundedness are bad. Without well-foundedness, it could be that each ground would need to be grounded in turn, and so the creation of a non-fundamental element of reality would never end up coming about because it would always require a further ground. Yet, given the fact regress, there can also be no stopping point—no point from which what’s grounded is ultimately able to be generated from its grounds. So determination, and hence what’s determined, would always be deferred and never achieved.

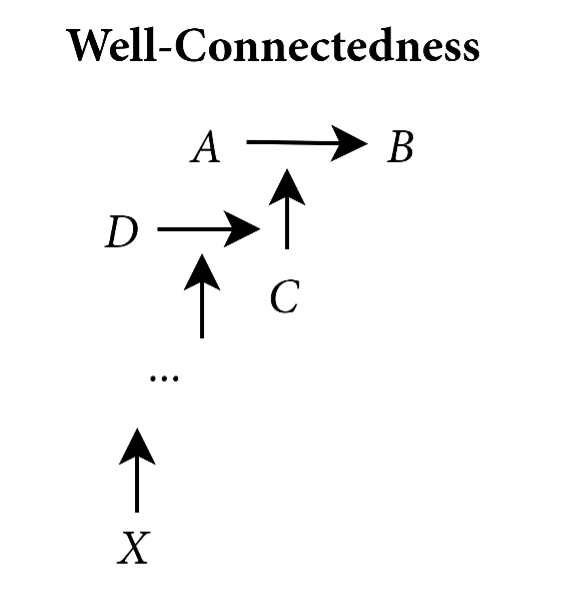

Therefore, I uphold well-connectedness, which requires that every path of grounding of grounding facts terminates in an ungrounded grounding fact:

This prohibits the fact regress.

Well-connectedness falls out of the proper interpretation of completeness, which imposes the requirement that the fundamental is enough for the non-fundamental. For any portion of non-fundamental reality, there is some portion of the fundamental that is ‘enough’ to produce it. If well-connectedness is violated, then there is no portion of fundamental reality that is sufficient unto itself to produce any bit of non-fundamental reality. There would always have to be a further determination of how the fundamental determines the non-fundamental. But at some point the grounding of grounding must stop. Some grounding facts must be fundamental.

However, the fact regress seems to fall out of completeness and purity. So what gives? I think the key is to see that the proper interpretation of purity doesn’t require that grounding facts be grounded.

There’s a distinction between what’s called factive and non-factive grounding. Roughly put, A non-factively grounds B if and only if given A then A generates B. A factively grounds B just in case A non-factively grounds B and A obtains. So it could be that A non-factively grounds B even if B doesn’t obtain since A doesn’t obtain. Thus, in a legitimate sense, the fact that A non-factively grounds B doesn’t ‘contain’ A or B, since that grounding fact can obtain without either A or B obtaining. We can think of the non-factive grounding facts as ‘mentioning’ the ground and ground without ‘containing’ them. But this is consistent with purity, since fundamental non-factive grounding facts don’t have any non-fundamental constituents.

Want more?

Read the full article at: https://journals.publishing.umich.edu/ergo/article/id/4664/.

About the author

Christopher Frugé is a Junior Research Fellow at the University of Oxford in St John’s College. He received his PhD from Rutgers. He works on foundational and normative ethics as well as metaphysics.