In this post, Mario Hubert and Federica Isabella Malfatti discuss their article recently published in Ergo. The full-length version of their article can be found here.

If humans were omniscient, there would be no epistemology, or at least it would be pretty boring. What makes epistemology such a rich and often controversial endeavor are the limits of our understanding and the breadth of our own ignorance.

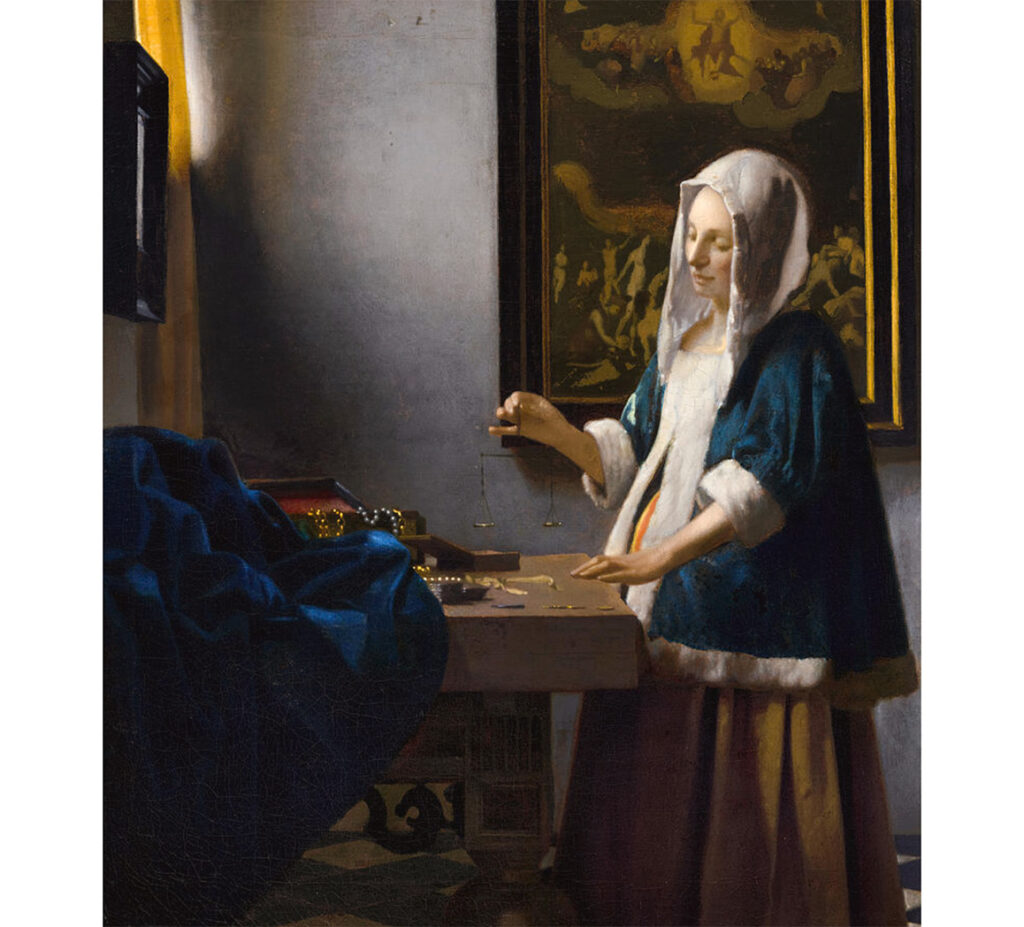

The world is like a large dark cave, and we are only equipped with certain tools (such as cameras, flashlights, or torches) to make particular spots inside the cave visible. For example, some flashlights create a wide light-cone with low intensity; others create a narrow light-cone with high intensity; some cameras help us to see infrared light to recognize warm objects, etc. From the snippets made visible by these tools, we may construct the inner structure of the cave.

The burden of non-omniscient creatures is to find appropriate tools to increase our understanding of the world and to identify and acknowledge the upper bound of what we can expect to understand. We try to do so in our article “Towards Ideal Understanding”, where we also identify five such tools: five criteria that can guide us to the highest form of understanding we can expect.

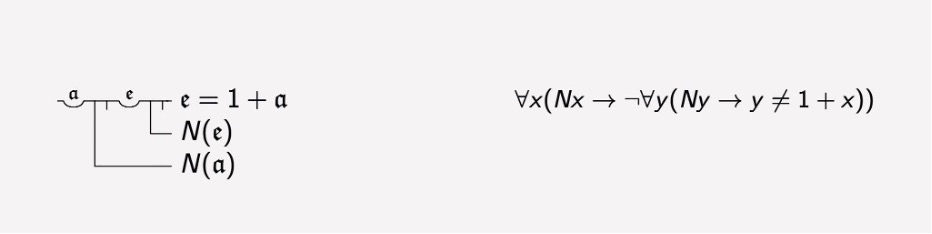

Imagine the best conceivable theory for some phenomenon. What would this theory be like? According to most philosophers of science and epistemologists, it would be:

- intelligible, i.e. easily applied to reality, and

- sufficiently true, i.e. sufficiently accurate about the nature and structure of the domain of reality for which it is supposed to account.

Our stance towards intelligibility and sufficient truth is largely uncontroversial, apart from our demand that we need more. What else does a scientific theory need to provide to support ideal understanding of reality? We think it also needs to fulfill the following three criteria:

- sufficient representational accuracy,

- reasonable endorsement, and

- fit.

The first criterion we introduce describes the relation between a theory and the world, while the other two describe the relation between the theory and the scientist.

We think that the importance of representational accuracy is not much appreciated in the literature (a notable exception is Wilkenfeld 2017). Some types of explanation aim to represent the inner structure of the world. For example, mechanistic explanations explain a phenomenon by breaking it up into (often unobservable) parts, whose interactions generate the phenomenon. But whether you believe in the postulated unobservable entities and processes depends on your stance in the realism-antirealism debate. We think, however, that even an anti-realist should agree that mechanisms can increase your understanding (see also Colombo et al. 2015). In this way, representational accuracy can be at least regarded as a criterion for the pragmatic aspect of truth-seeking.

How a scientist relates to a scientific theory also matters for a deeper form of understanding. Our next two criteria take care of this relation. Reasonable endorsement describes the attitude of a scientist toward alternative theories such that the commitment to a theory must be grounded in good reasons. Fit is instead a coherence criterion, and it describes how a theory fits into the intellectual background of a scientist.

For example, it might happen that we are able to successfully use a theory (fulfilling the intelligibility criterion) but still find the theory strange or puzzling. This is not an ideal situation, as we argue in the paper. Albert Einstein’s attitude towards Quantum Mechanics exemplifies such a case. He, an architect of Quantum Mechanics, remained puzzled about quantum non-locality throughout his life to the point that he kept producing thought-experiments to emphasize the incompleteness of the theory. Thus, we argue that a theory that provides a scientist with the highest conceivable degree of understanding is one that does not clash with, but rather fits well into the scientist’s intellectual background.

The five criteria we discuss are probably not the whole story about ideal understanding, and there might be further criteria to consider. We regard the above ones as necessary, though not sufficient.

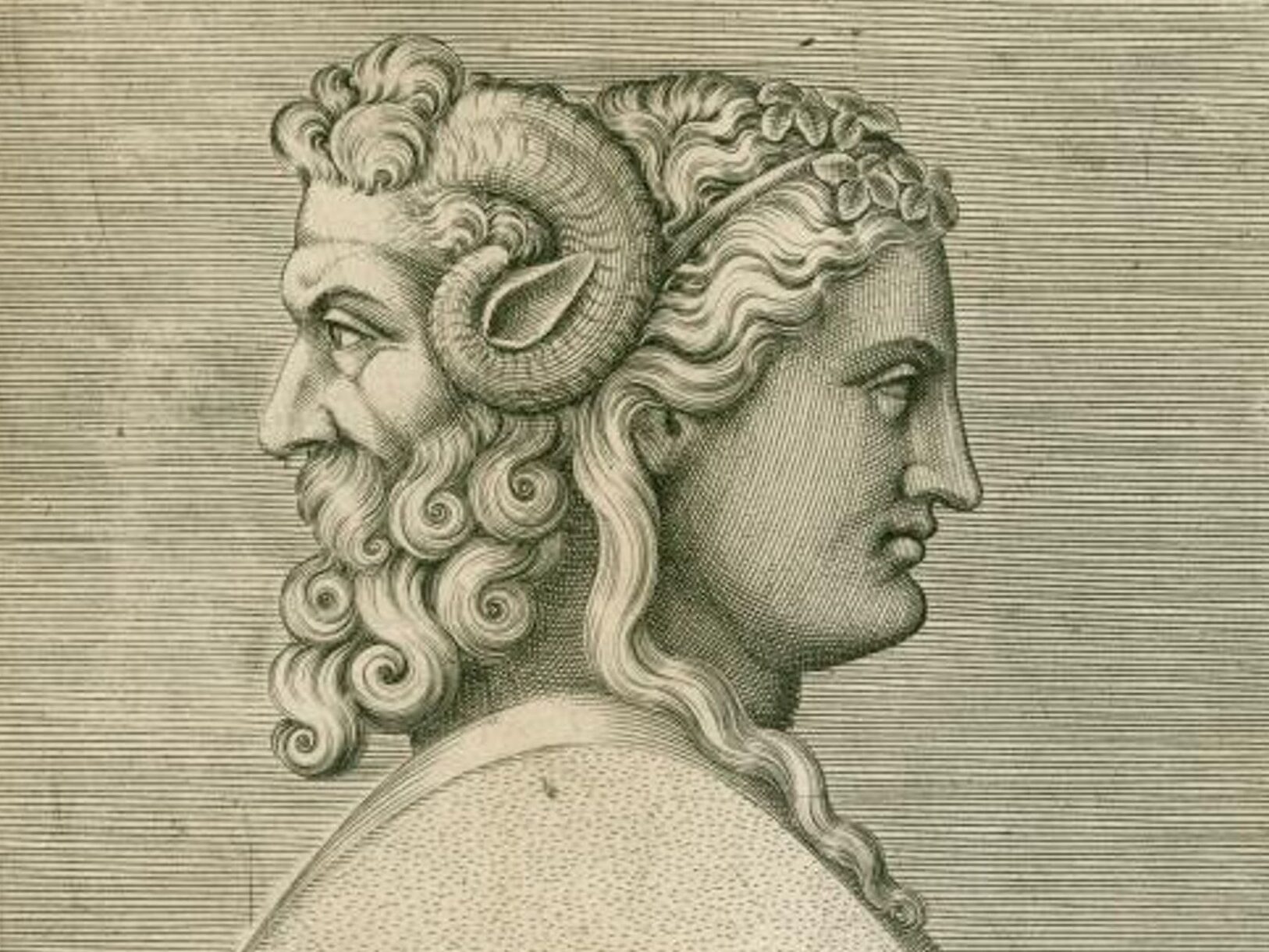

An objector might complain: If you acknowledge that humans are not omniscient, then why do you introduce ideal understanding, which seems like a close cousin of omniscence? If you can reach this ideal, then it is not an ideal. But if you cannot reach it, then why is it useful?

Similar remarks have been raised in political philosophy about the ideal state (Barrett 2023). Our response is sympathetic to Aristotle, who introduces three ideal societies even if they cannot be established in the world. These ideals are exemplars to strive for improvement, and they are also references to recognize how much we still do not understand. Furthermore, this methodology has been the standard for much of the history of epistemology (Pasnau 2018). Sometimes certain traditions need to be overcome, but keeping and aspiring to an ideal (even if we can never reach it) seems not to be one of them… at least to us.

Want more?

Read the full article at https://journals.publishing.umich.edu/ergo/article/id/4651/.

References

- Barrett, J. (2023). “Deviating from the Ideal”. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 107(1): 31–52.

- Colombo, M., Hartmann, S., and van Iersel, R. (2015). “Models, Mechanisms, and Coherence”. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 66(1): 181–212.

- Pasnau, R. (2018). After Certainty: A History of Our Epistemic Ideals and Illusions. Oxford University Press.

- Wilkenfeld, D. A. (2017). “MUDdy Understanding”. Synthese, 194(4): 1-21.

About the authors

Mario Hubert is Assistant Professor of Philosophy at The American University in Cairo. From 2019 to 2022, he was the Howard E. and Susanne C. Jessen Postdoctoral Instructor in Philosophy of Physics at the California Institute of Technology. His research combines the fields of philosophy of physics, philosophy of science, metaphysics, and epistemology. His article When Fields Are Not Degrees of Freedom (co-written with Vera Hartenstein) received an Honourable Mention in the 2021 BJPS Popper Prize Competition.

Federica Isabella Malfatti is Assistant Professor at the Department of Philosophy of the University of Innsbruck. She studied Philosophy at the Universities of Pavia, Mainz, and Heidelberg. She was a visiting fellow at the University of Cologne and spent research periods at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and UCLA. Her work lies at the intersection between epistemology and philosophy of science. She is the leader and primary investigator of TrAU!, a project funded by the Tyrolean Government, which aims at exploring the relation between trust, autonomy, and understanding.