In this post, Daniel Buckley discusses his article recently published in Ergo. The full-length version of Daniel’s article can be found here.

According to one prominent view, a necessary condition for the appropriateness of holding someone responsible for their conduct (e.g. through moral blame) involves disclosure of an objectionable feature of their (“true”, “deep”, or “real”) self, where the latter consists, roughly, of the person’s values, ends, and commitments. This is the kind of condition which is plausibly unmet in a case where a person’s action causes harm to others, but where the person performing the action manifested no malice, ill-will, or disregard. For instance, perhaps at the time of acting this person was, through no fault of their own, simply ignorant of the likely objective consequences of their action. Contrast this with a case where a person’s action causes harm to others, but where the person performing the action was fully aware of its likely objective consequences. Perhaps their action was underwritten by an egregious disregard for the well-being of others, or by an explicit intention to harm people. The idea is that moral accountability responses like blame are perhaps called for in this latter kind of case, but not in the former, in virtue of the fact that the conduct expressed objectionable values, ends, and commitments, i.e. an objectionable “self”.

The aim of my paper is to investigate the relevance of self-disclosure for epistemic responsibility. The central question that I explore is the following: Is it the case that, in order to appropriately hold a person epistemically responsible, the person must express or disclose an objectionable doxastic self?

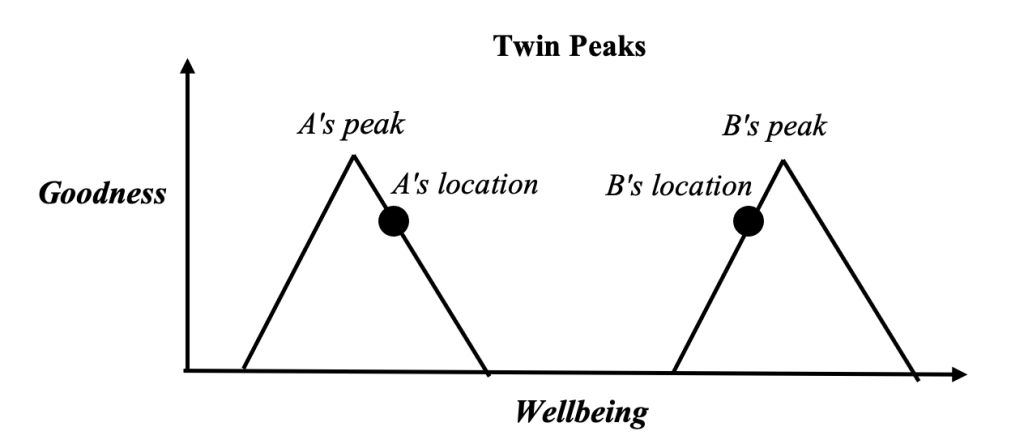

As I understand it, a person’s “doxastic self” consists of values, ends, and commitments which pertain to the maintenance and regulation of their beliefs. So, for instance, a diligent and conscientious doxastic self might include a commitment to carefully weigh the evidence, avoid biases and fallacies, etc. A reckless and dogmatic doxastic self, on the other hand, might be characterized by a tendency to draw hasty conclusions, cherry pick evidence, etc. I argue for a negative answer to the above question. In other words, my view is that a person can be appropriately held epistemically responsible even if they have revealed nothing objectionable about their “doxastic self”, so understood.

Consider the following two cases which frame much of my discussion:

Stubborn Sam: Sam has an abundance of available evidence which is such that, were he to consider it more carefully, he would feel rationally compelled to abandon his denial of the existence of human-induced climate change. However, Sam doesn’t consider this evidence more carefully and, as a result, he maintains his belief that human-induced climate change isn’t real.

Diligent Doug: Doug lives in a community run by a group of individuals who have managed to shut off access to evidence pertaining to the existence of human-induced climate change. Doug is interested in forming true beliefs about this topic, frequently going to the library to research it. Nevertheless, given the evidence available to him, Doug believes that human-induced climate change isn’t real.

Unlike Sam, Doug does not reveal an objectionable doxastic self in believing as he does; he is a conscientious and responsible believer who is doing his best to respond to the available evidence. In spite of this, I argue that Doug can be appropriately held responsible for believing that human-induced climate change isn’t real.

Sam can of course also be held responsible for believing that human-induced climate change isn’t real. What’s more, the accountability responses that can be appropriately adopted towards Sam may amount to a distinctly epistemic form of blame (I am willing to grant this). My view is that Doug is also an appropriate target of distinctly epistemic accountability responses.

Importantly, I do not argue that Doug is blameworthy for believing as he does. Thus, one claim that I defend is that the epistemic domain involves accountability responses which can be appropriately adopted towards an individual even when that person is in no way blameworthy.

What is it, though, to hold a person responsible in a distinctly epistemic manner? Here I follow Boult (2021) and Kauppinen (2018) in thinking that adjusting my trust in an individual is a way of holding that person responsible in a distinctly epistemic manner. For instance, I might cease to take a person’s words at face value when it comes to certain topics or subject matters (e.g. climate change).

Interestingly, both Boult and Kauppinen suggest that this kind of trust modification only constitutes a genuine accountability response in cases where the person in question manifests an objectionable doxastic self (e.g. Stubborn Sam). Here I disagree: this kind of trust modification can also constitute a genuine accountability response in cases where the person does not manifest an objectionable doxastic self (e.g. Diligent Doug).

My hope is that this paper advances our understanding of epistemic responsibility and contributes to broader discussions of epistemic normativity, especially those which connect the latter with our social practices.

References

- Boult, Cameron. (2021). “There is a Distinctively Epistemic Kind of Blame”. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 103(3), 518–534.

- Kauppinen, Antti. (2018). “Epistemic norms and epistemic accountability”. Philosophers Imprint, 18(8).

About the author

Daniel Buckley is currently Assistant Teaching Professor at Penn State Harrisburg. His research focuses on issues in ethics and epistemology, especially questions concerning normativity, agency, and responsibility.